Album By Album – OMD

By Mark Lindores | November 15, 2023

The synth-pop icons who mastered the blend of experimentalism and melody…

The synth-pop icons who mastered the blend of experimentalism and melody…

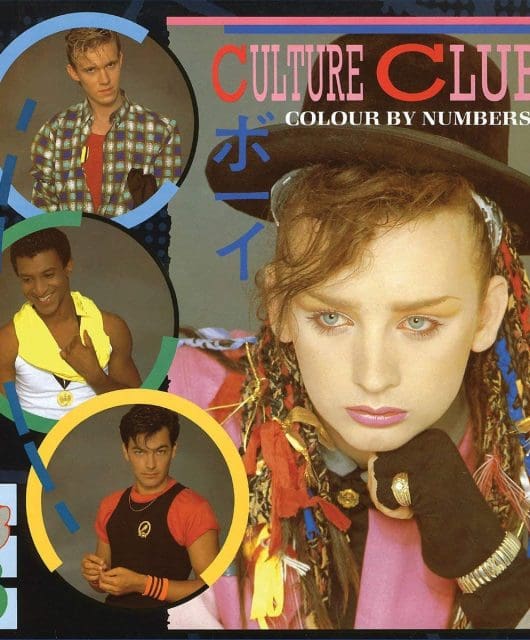

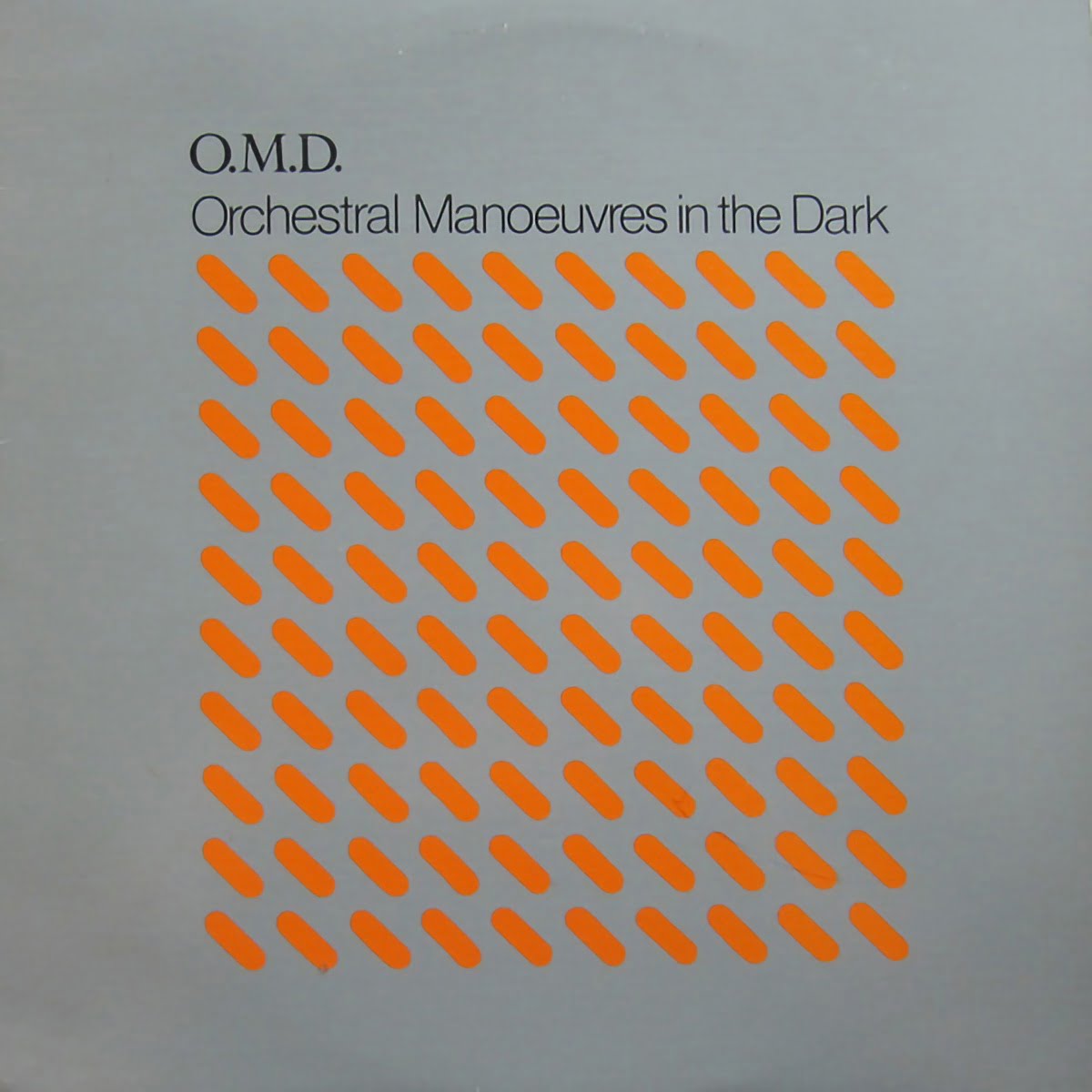

Orchestral Manoeuvres In The Dark, 1980

Thanks to Liverpool’s hosting of this year’s Eurovision Song Contest, 2023 has already seen Merseyside’s musical heritage celebrated for its greatness.

And with the Wirral’s Orchestral Manoeuvres In The Dark – an oft-overlooked inclusion in conversations such as these despite a back catalogue of scintillating synth-pop – toasting their 45th anniversary this year, the celebrations should continue a little while longer.

While former schoolfriends Andy McCluskey and Paul Humphreys had both been in bands around Liverpool, a mutual adoration of experimental electronica such as Kraftwerk, Brian Eno and Neu! saw their paths align, first in The Id, then OMD in 1978.

Early shows at iconic venues Eric’s in Liverpool and The Factory club in Manchester created a buzz, amplified when Factory Records’ Tony Wilson declared them “the future of pop” and signed them to a one-single deal for Electricity purely to get them noticed by the major labels.

Wilson’s namesake, Carol Wilson, signed OMD to her Dindisc label. Talking with omd-messages.co.uk Carol said: “He gave me the band because he felt they needed a label with a more commercial approach. People thought we were married to each other, but we never even snogged.”

Signing with the Virgin imprint granted the band the creative freedom of an indie with the financial security of a major. Speaking of security, the band weren’t confident of long-term success and used their advance to build The Gramophone Suite, their own studio in Liverpool.

Their eponymous debut was released in February 1980, a collection that set a template for the OMD sound – obtuse arrangements and experimental instrumentation with pop hooks relaying lyrics scoping everything from catastrophic events such as nuclear war (Bunker Soldiers) to the local telephone box which temporarily served as OMD HQ (Red Frame/White Light).

A re-recorded version of Electricity is a seminal synth-pop masterpiece and introduces an oft-used OMD trademark of replacing a chorus with an instrumental sequence.

Messages, with its sweeping beat punctuated by recurring beeps and the sparse Almost, a track cited by Vince Clarke as the reason he pursued a career in electronic music, repeat the sonic structure.

OMD’s strait-laced image was far removed from the flamboyance of the New Romantic scene with which synth-pop was sometimes linked; Andy and Paul were more ties and tank tops than togas and tiaras, further establishing them as an entity entirely of their own.

Likewise, with the clean graphics of their artwork, courtesy of Peter Saville’s crisp die-cut sleeve, a masterstroke of graphic design but a disaster business-wise due to the production costs.

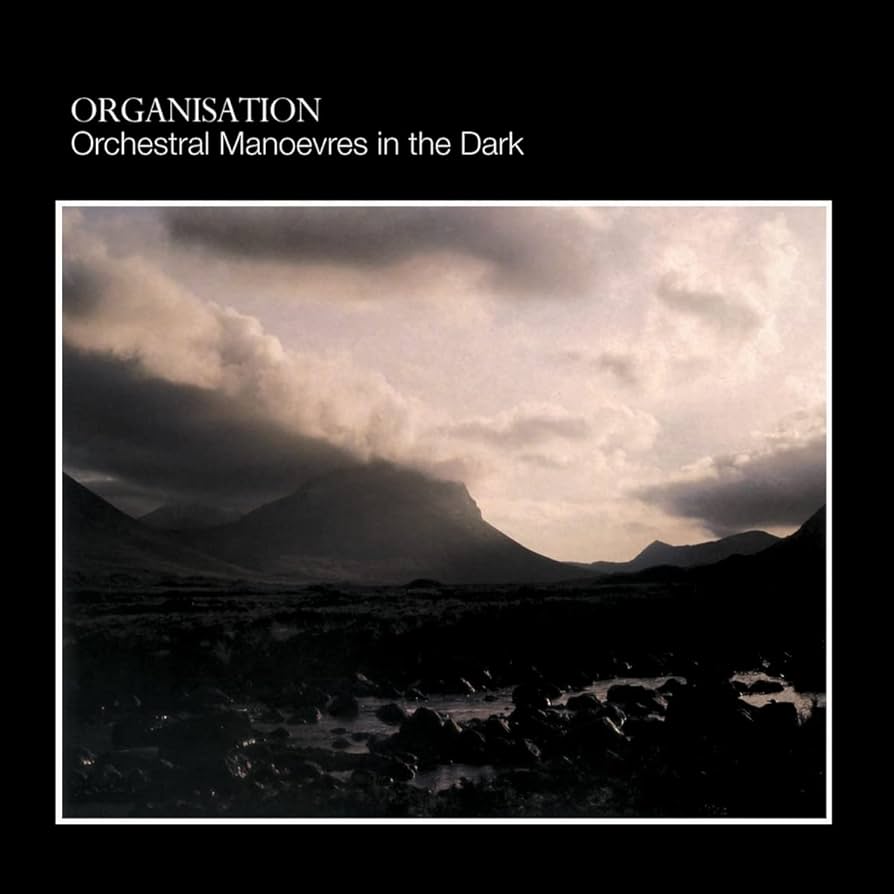

Organisation, 1980

Facing record company pressure to deliver another album before the end of 1980 and reeling from the suicide of one-time labelmate and touring partner Ian Curtis from Joy Division, the Organisation sessions were far from easy for Andy, Paul and drummer Malcolm Holmes, who had been recruited as a full-time band member – Holmes had previously played on earlier records as a session drummer and toured with OMD.

Nevertheless, the group found beauty amid the bleakness and crafted a record of enormous scope – atmospheric and ambitious.

While resources and lack of money had forced them to improvise with everyday objects for sound effects on earlier songs, for Organisation their music was augmented with samples – most notably on Stanlow, a track written about the oil refinery in Ellesmere Port where McCluskey’s father and sister worked.

Recordings of the machinery and pumps included on the record elevated it to evoke dark industrial soundscapes, desolation and diminishing communities.

Due to a tight deadline that hindered the writing of new material, the album includes a cover of standard The More I See You, and other songs from the pre-OMD days of The Id were reworked for inclusion, while Statues, inspired by the death of Ian Curtis, immortalised the tragic events of the time.

Both the album’s title and VCL XI paid homage to their love of Kraftwerk (Organisation being the name of a pre-Kraftwerk line-up, the latter the name of a valve on the back sleeve of the electro pioneers’ 1975 album Radio-Activity).

By far the standout track, though, is the lone single Enola Gay. In contrast to the gloomy mood pieces that formulate the majority of the album, Enola Gay is an upbeat, punchy, danceable song on face value, until you realise it’s about the aircraft that dropped the bomb on Hiroshima during World War II.

The song reached No.8 in the UK singles chart, giving OMD their first Top 10 hit. Its parent album Organisation, released in October 1980, and just eight months after their debut long-player, achieved No.6 in the UK albums chart. OMD were up and running as a pop force…

Architecture & Morality, 1981

Having mastered the art of penning earworms with Electricity and Enola Gay, some of the darker-leaning material on Organisation had proved too experimental for a portion of OMD’s fans.

For their third LP, they set out to strike a balance between the two extremes.

The impetus of the LP came when the band received clips of choir recordings as payment for use of their studio from former OMD session musician Dave Hughes and came up with the idea of integrating them into their music.

Excited by the juxtaposition of the emotional pull of the choral voices against the mechanical synths, a direction had been established (the ‘architecture’ of the album’s title is the sonic backdrop with the ‘morality’ coming from the monastical voices).

A distillation of everything the band had learned to date with regards to song structure and texture, the album was a perfect summation of their keenness for avant-garde sonics teamed with catchy melodies.

The first song recorded, Souvenir, was a natural choice as lead single. A shimmering slice of synth-pop fleshed out with the choral samples acting as backing vocals, it still stands as one of OMD’s finest moments.

Expressing an aversion to straightforward love songs, Joan Of Arc and Maid Of Orleans both lamented the French saint with the bagpipe-laden waltz of the latter proving particularly successful.

Elsewhere on the LP, the sprawling Sealand puts Eno-esque atmospherics at the forefront before building to a minimal mantra-like vocal as the song approaches its conclusion.

The haunting title track and The Beginning And The End make further use of the choral clips before the exuberance of Georgia provides a respite from the heavy melodrama.

She’s Leaving, a homage to The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s track She’s Leaving Home, is another standout here, while the jaunty opener The New Stone Age, with its jagged guitars affirmed OMD’s eclecticism – they joked they wanted their fans to think the wrong record had been put in the sleeve.

Reaching No.3 in the UK Albums Chart and spawning three Top 5 singles in Souvenir, Joan Of Arc and Maid Of Orleans, with Architecture & Morality, OMD had created a synth-pop masterpiece.

Dazzle Ships, 1983

Tasked with replicating the commercial success of second album Architecture & Morality, along with bewilderment at those sales levels and writer’s block, meant that 1983’s Dazzle Ships proved to be OMD’s first major obstacle. In fact, mounting pressures on Paul and Andy were so immense that the band’s future was in jeopardy.

Feeling obligated to carry on by the support of their fans, they maintained their stance on never repeating themselves, and delivered an album in stark contrast to its predecessor.

The singles, Genetic Engineering and Telegraph, along with Radio Waves, are the poppiest moments of a concept record which is at large a musical mosaic of abstract electronics, cut-and-paste radio announcer samples and ambient mood pieces.

In the midst of some self-indulgence (Time Zones, ABC Auto-Industry), there is a lot to love. The Romance Of The Telescope is a beautiful ballad, which soon unfolds to reveal the familiar marching band and monastical vocals of Architecture & Morality before segueing into the yearning Silent Running.

Underrated at the time of its release, Dazzle Ships has since undergone critical reappraisal. Although it reached a respectable No.5 in the UK, it only managed to sell a fraction of its predecessor and duly forced OMD to retreat from such bold experimentalism on future projects.

Junk Culture, 1984

Both in creation and its reception, Dazzle Ships had, by the group’s own admission, almost brought the OMD story to an end. As well as the fraught, tension-filled creative process, Paul Humphreys told Melody Maker at the time that sales of that record indicated it had cost them “almost 90% of our audience”. Therefore, a rethink was not only recommended, it was essential.

Described as a make-or-break record, 1984’s Junk Culture saw the group pivot to a much more commercial sound and access different influences – a direct reaction to their environment. Wanting to get out of their own heads, they also chose to record outside of their own Gramophone Suite studios.

As well as sessions in Inverness, London and Lincolnshire, it was a spell at George Martin’s AIR Studios in Montserrat (a sojourn to avoid a hefty tax bill for Architecture’s mammoth sales) that had the most significant impact.

In the paradisical surroundings of the Caribbean, the rich culture permeated the sound of the record, with dub and reggae accents making their way onto the album.

The group had already proved their versatility and their collage-like approach to texture worked just as well with tropical affectations as it did with machinery or radio announcements. The one constant was their ability to create memorable pop melodies – and Junk Culture has those in spades.

Lead single Locomotion, with its unforgettable chorus and steel drums, could not have been more of a palate cleanser from Dazzle Ships.

Likewise with the hi-NRG Tesla Girls and its stuttering Blue Monday-esque drum pattern and soaring melody plus the dubby, languid lead of the title track.

Similarly, the spacey, reggae-inflected White Trash bears all the hallmarks of OMD’s island life while their acquisition of the new Fairlight CMI resulted in the sublime Talking Loud And Clear.

Any worries that the alienation of their audience was permanent were swiftly alleviated upon the album’s release in April 1984

It crashed into the UK Top 10 amid a positive critical reception and produced four singles. Equal to that commercial success was the affirmation of what OMD fans wanted from them, invaluable to their long-term future.

Crush, 1985

Though it has often been the case that OMD albums seem to be a direct reaction to the previous one, Crush saw them heading further down the same avenue as Junk Culture in terms of commercial, radio-friendly pop. In fact, for much of the album, it is only Andy McCluskey’s distinctive voice that equates it with early OMD.

Teaming with producer Stephen Hague for the first time, it’s unsurprising that the album’s slick production aims directly at the US market – a move that was at least partially successful, as the record itself and So In Love, its lead single, gave the band their first Top 40 successes Stateside.

Although many of the songs were demoed using the Fairlight CMI, they were later re-recorded using more organic instrumentation in a bid to capture the live sound of the band.

Another big change was the lyrics. Having previously sung about everything from telephone boxes and oil refineries to historical figures rather than generic love songs, McCluskey’s relationship with future wife Toni informed much of the album (also giving Crush its title).

So In Love is the obvious standout, but Secret (the album’s second single) and 88 Seconds In Greensboro maintain the high standard. The sparse, sample-laden title track and closing The Lights Are Going Out are the closest the album gets to the ‘traditional’ electro OMD sound.

The Pacific Age, 1986

The US success that was accumulated from Crush and If You Leave – thanks to the latter featuring prominently in the Pretty In Pink movie – turned out to be a double-edged sword.

OMD were already an entity known for their tireless work ethic (The Pacific Age was their seventh studio LP in six years) and the band were pushed to breaking point.

Crush’s success across the pond meant their US label A&M was keen to build on that foundation and were pressurising OMD for a quick follow-up.

With relationships among the band members already at a low point, problems pertaining to drugs and alcohol and a short deadline for the album meant that the environment to create could not have been worse. And it shows in the resulting record.

A continuation of the glossy, bombastic pop of Crush, with Stephen Hague returning on production duties, The Pacific Age all but wipes out OMD’s original identity, stripping it of everything that made them unique – an unfortunate turn of events for an act that previously had been ahead of the curve.

Opener Stay (The Black Rose And The Universal Wheel) is practically a pastiche of Duran Duran circa 1983 while the title track is derivative of sounds that the band had done so much better previously.

The album’s biggest hit (Forever) Live And Die is the obvious highlight and We Love You is a harmless slice of Americanised pop/rock but both pale in comparison to their previous work.

Subsequently, both Humphreys and McCluskey have spoken negatively about The Pacific Age, with Paul describing it as their “musical nadir” in the 2014 book Mad World: An Oral History Of New Wave Artists And Songs That Defined The 1980s. He went on to say it contained songs and lyrics that they would have been appalled by previously.

Despite being obviously geared towards the US market, The Pacific Age peaked at a disappointing No.47 there. Burnt out, creatively spent and feeling they had compromised themselves for something that hadn’t succeeded artistically, it marked the beginning of the end. As an album closer, Watch Us Fall could not have been more apt.

Sugar Tax, 1991

The new decade marked something of a rebirth for OMD. 1986’s The Pacific Age had proved commercially and creatively unfulfilling and, having worked relentlessly throughout the first half of the 80s, both Humphreys and McCluskey decided to take a break from OMD.

The release of a greatest hits collection in 1988 was a stellar reminder of their bulletproof canon of singles. The compilation’s inclusion of new track Dreaming (a massively underrated OMD anthem) would prove to be Paul’s swansong.

He left the band, along with Martin Cooper and Malcolm Holmes to form The Listening Pool, leaving Andy McCluskey to continue with a new line-up.

Hesitant and fearful of carrying on the group’s musical legacy essentially as a solo artist with contributions from session musicians, McCluskey credited everything – writing and producing – to OMD as had always been the case.

Recorded in London and Liverpool over the course of two years, it was a far cry from the pressurised time constraints of previous albums. McCluskey’s luxury of working at his own pace proved hugely beneficial, allowing him to experiment more.

Released in May 1991, the campaign got off to a great start with the release of lead single Sailing On The Seven Seas two months earlier.

glam-infused stomper with an anthemic chorus, it immediately stands out not only as the album highlight but also as one of OMD’s greatest tracks.

Second single Pandora’s Box followed the trope of Elton John’s Candle In The Wind, replacing Marilyn Monroe with Louise Brooks to illustrate the toxic side of Hollywood stardom over a Eurodance beat that also forms the backdrop for Call My Name.

The beautiful, soaring Speed Of Light is a continuation of that sound and proves to be another highlight and proof that McCluskey’s ear for killer melodies was as sharp as ever.

Apollo XI combines a dance beat with samples of dialogue from reporting of space missions (evoking Dazzle Ships’ electro experimentalism) while Neon Lights is a Kraftwerk cover to pay homage to Andy’s biggest musical inspiration.

Achieving sales of over three million copies, Sugar Tax was the strongest OMD album in years and houses its fair share of career highlights.

Liberator, 1993

Re-energised and on a high after the huge success of Sugar Tax, Andy McCluskey went back into the studio to record a follow-up.

Taking the more dance-inflected hits of that record as a basis for Liberator, the album dials up its reliance on Eurodance, house-lite instrumentation which unfortunately fails to mask the lack of hooks and melodies that made OMD’s previous album such a success.

Lead single and opener Stand Above Me, Love And Hate You and Dollar Girl come off as reductive attempts to recapture Pandora’s Box, while the album’s third single Everyday sounds particularly dated – it comes as no surprise that it was a reworked track from 1987 (hence the songwriting credit for Paul Humphreys). Heaven Is is also a reworked version of a song first performed in 1983.

The cover of The Velvet Underground’s 1966 single Sunday Morning is disastrous in every way, with the awful synthetic instrumentation evoking the worst of Robson & Jerome.

Given the severity with which Duran Duran were later lambasted for their take on Lou Reed’s Perfect Day, the fact that this remained an album track was fortunate.

Agnus Dei and Heaven Is are cluttered amalgamations of ideas, none of which are particularly good. Pounding dance beats and tacky ‘rave’ synths are here in abundance, and you can’t help but wonder if, despite the album’s title, the band were trapped by the notion of sounding ‘relevant’.

The album’s only real saving graces are the mellow swingbeat of King Of Stone, with its synthesised vocal tracks and Dream Of Me (Based on Love’s Theme), which includes a sample of Love Unlimited Orchestra’s Love’s Theme, but even that doesn’t quite reach the heights of some of the band’s previous gorgeous ballads.

The album peaked at No.14 in the UK and two of its three singles charted on home soil – Stand Above Me (No.21) and Dream Of Me, which made No.24.

Liberator was promoted via an arena tour with Gary Numan as their supporting act – a full circle moment as OMD supported him when they were first starting out back in 1979.

Universal, 1996

A return to form, 1996’s Universal saw McCluskey dispense with the awful techno leanings of Liberator and draw on his strengths: writing catchy pop melodies and incorporating music to complement them rather than bury them.

Released at the peak of Britpop, Universal landed right at the centre of contemporary music, though it suffered with its creators being regarded as old-fashioned due solely to their longevity.

First single Walking On The Milky Way deserved to be a much bigger hit than its No.17 UK peak but did well regardless of the lack of radio support.

Elsewhere, the album is littered with gems, touching on doomed love, the passing of youth and disillusionment.

The stunning Too Late manages to sound like both The Police and China Crisis while The Boy From The Chemist Is Here To See You captures Different Class-era Pulp (producers Matthew Vaughan and David Nicholas both worked on that album).

Which isn’t to say Universal is a pick‘n’mix of other artists. At its core it is still unmistakeably an OMD record and many of the highlights capture their own former glories, from the beautiful, string-laden atmospherics of The Black Sea to sombre closer Victory Waltz.

The latter is a tender piano ballad, which culminates in a choral climax. Well worth seeking out for reappraisal.

History Of Modern, 2010

While 1996’s Universal suffered due to OMD being regarded as ‘unfashionable, by 2010, everyone from The Killers to LCD Soundsystem and The XX were citing them as an influential touchstone. It introduced the band to a new generation of fans.

McCluskey was back in OMD mode having taken some time out to mentor Atomic Kitten, and reunited with Humphreys, Cooper and Holmes – aka ‘the classic line-up’ – for a documentary, tour and reappraisal of their earlier work. The timing was perfect for the first new OMD album in 14 years – or 24 years for this formation of the band.

History Of Modern, although very much steeped in their past, sounded contemporary due to the 80s revisionism that was all the rage at the time (and still is).

New Babies; New Toys, Green, RFWK and Sometimes all hark back to the early-80s albums of sparse synth-pop while The Future, The Past, And Forever After is more in alignment with the slick dance pop of the Sugar Tax era of the early 90s.

Pulse would be more suited to a young female pop ingénue and The Right Side? is an eight-minute sprawling montage of synths and filtered vocal layers. US bonus track Save Me is an unexpected delight, OMD’s electronic cover of the Aretha Franklin classic containing her stunning original vocals.

English Electric, 2013

Though 2010’s History Of Modern album marked the reunion of the classic line-up on record for the first time in over two decades, the fact that it was created remotely (a decade ahead of their time on that score as the whole world would be forced to work that way in 2020) slightly diminished its impact.

For English Electric, McCluskey and Humphreys went back to their roots writing and recording everything in person in a bid to recapture the hunger of the early albums.

The experiment worked as English Electric emerges as a collection that immediately ranks in the upper echelons of OMD’s discography. Sounding completely current, the crisp synths, driving bass and eclectic electronics all accentuate their superb songwriting.

A single listen to the likes of Dresden, Stay With Me (Humphreys’ first OMD lead vocal in more than 20 years) and Metroland and they are immediately lodged in your brain.

Kissing The Machine (a cover of a track by Elektric Music, a band featuring Kraftwerk’s Karl Bartos) contains a stunning special guest appearance from Propaganda’s Claudia Brücken while Helen Of Troy updates Joan Of Arc.

Our System begins as a lone ballad before building to a choral crescendo replete with tribal drums not dissimilar to Simple Minds’ Alive And Kicking.

Always a master at creating lyrical melodrama, McCluskey’s personal situation – his divorce from his wife and her relocating to America with their children – provided a wealth of material for some of the album’s more melancholic moments.

Though not a nostalgic record at all, English Electric does contain a few nods to the past for OMD purists, some more blatant than others.

Atomic Ranch, The Future Will Be Silent and Please Remain Seated are direct descendants of Dazzle Ships with their severed voice notes over beeps and beats.

Released in April 2013, the album was met with near unanimous critical praise, likening it to their ground-breaking early records – most notably Dazzle Ships (which has since been reassessed as a revered, experimental classic) and Architecture & Morality.

Four singles, Metroland, Dresden, The Future Will Be Silent and Night Café were pulled from the LP which reached No.12 in the UK.

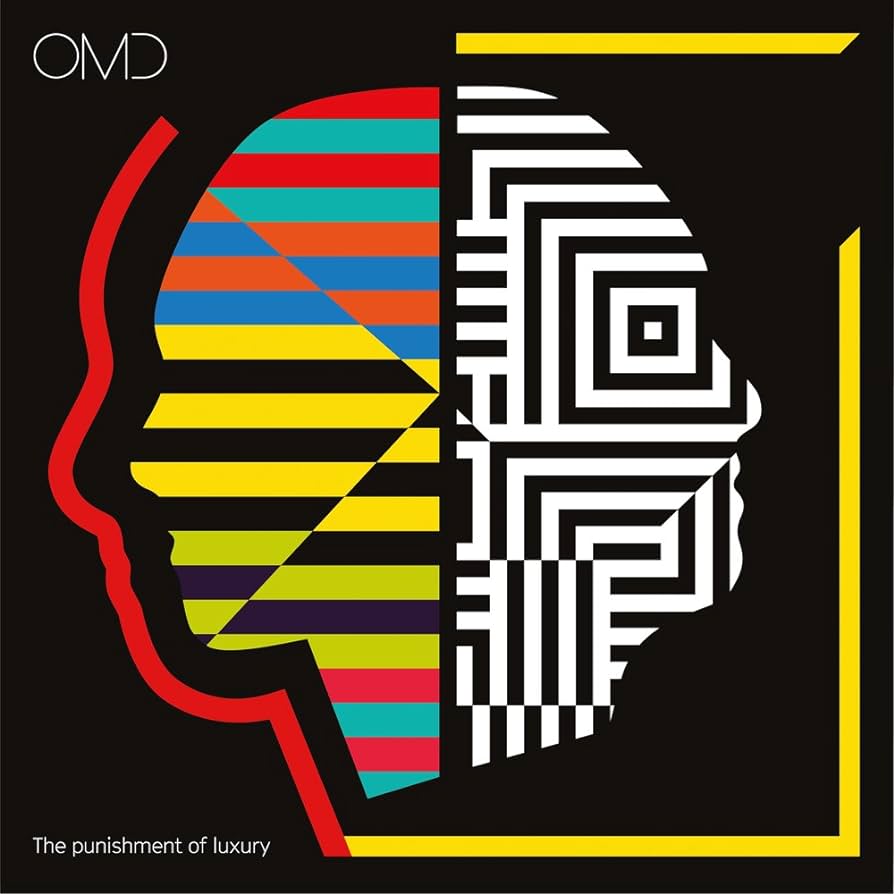

The Punishment Of Luxury, 2017

Having toured extensively to promote English Electric, by 2015, Paul and Andy had already begun work on a follow-up.

Having toured extensively to promote English Electric, by 2015, Paul and Andy had already begun work on a follow-up.

While their last album had referenced their own back catalogue fed through a modern filter with astonishing results, The Punishment Of Luxury (an abstract way of saying ‘First World problems’) sees the band revert back even further to pay homage to the music that inspired them originally – most notably Kraftwerk, with the ghosts of the men machines looming large throughout the project.

Art Eats Art even sees them distorting their vocals in the style of the Düsseldorf four-piece’s seminal The Robots. While that is possibly the most blatant reference to their heroes, nods are littered throughout the album, be it in its sparse electronics or structure.

Kiss, Kiss, Kiss, Bang, Bang, Bang pulses with electricity, One More Time is a beautiful, wistful ballad which OMD have always excelled at, as is What Have We Done (the strongest melody on the record).

Robot Man deals in emotional detachment and teams tough beats with squealing synth stabs while La Mitrailleuse (French for ‘machine gun’) begins with a monotone voice before machine-gun fire disturbs the peace.

Ghost Star is a mellow track bathed in synths and birdsong and the hypnotic dance of Isotype is a standout, the obvious choice for first single. It was the first of four, with the title track, What Have We Done and One More Time following.

Although very much a continuation of the future nostalgic sound they began on English Electric, The Punishment Of Luxury does fall short of that album in terms of both ideas and execution (occasionally it’s too minimal).

However, it is still a very strong record and a superb testament to OMD that they have fought the perception of what a legacy artist is.

Bauhaus Staircase, 2023

Just when they thought they could enjoy a cosy semi-retirement of performing old songs on tour, safe in the knowledge that their final LP, The Punishment Of Luxury, was a hell of a last studio statement, lockdown significantly changed Andy McCluskey and Paul Humphreys’ lives.

Just when they thought they could enjoy a cosy semi-retirement of performing old songs on tour, safe in the knowledge that their final LP, The Punishment Of Luxury, was a hell of a last studio statement, lockdown significantly changed Andy McCluskey and Paul Humphreys’ lives.

For Humphreys, new fatherhood meant he had even less impetus to drag himself back to the studio. For McCluskey, however, total boredom meant he was becoming restless again. Like a frustrated teenager, he began stomping to his room to write songs, in order to have something to do.

Sure enough, there’s a definite air of bored teen to OMD’s first album in six years. It’s a record they clearly had to make, because they’d have driven themselves mad otherwise.

McCluskey’s nihilism is most obvious on Kleptocracy and Slow Train, the two songs Humphreys didn’t have time to mix, leaving rock producer David Watts to finish.

Cleaving to McCluskey’s most route-one teenage love of glam, they’re big dumb synth-pop songs about, respectively, socialism and nothing at all, except for the need to sing “Na-na-na” for three minutes.

If they’re deliciously unsubtle, don’t assume this is a McCluskey solo album in all but name. When he does contribute, Humphreys is reliably fantastic. Veruschka is the kind of elegant mystery OMD have traded in for 45 years.

You can unpick its film noir references easily enough, but it doesn’t explain how Humphreys’ melody is so perfectly balanced between terror and glacial beauty, even though it’s a dividing line familiar from so many past OMD songs.

Look At You Now and Where We Started are similarly beautiful ballads all the more affecting because of McCluskey’s initially offhand, conversational delivery.

Written during a since-vanished romance, Aphrodite’s Favourite Child ratchets up the tension, its simple structure only serving to highlight how intense McCluskey’s declarations of love are.

It’s impressive the ballads are still at home on an album that’s the duo’s most explicitly political. Anthropocene and Evolution Of Species are companion pieces about evolution that cleverly use Google’s Text-To-Speak function, very much in the spirit of early electronics.

The title track is another simple pop song, yet its warnings about “fascist art” are a clear message about the necessity of culture during tough times. And, if you want straight-up pop, G.E.M. is a stunning diss track that could be by Suzi Quatro.

Pretty much any song here will fit right in next to Maid Of Orleans and Locomotion. If Bauhaus Staircase is OMD’s final album, it’s a hell of a last studio statement. John Earls