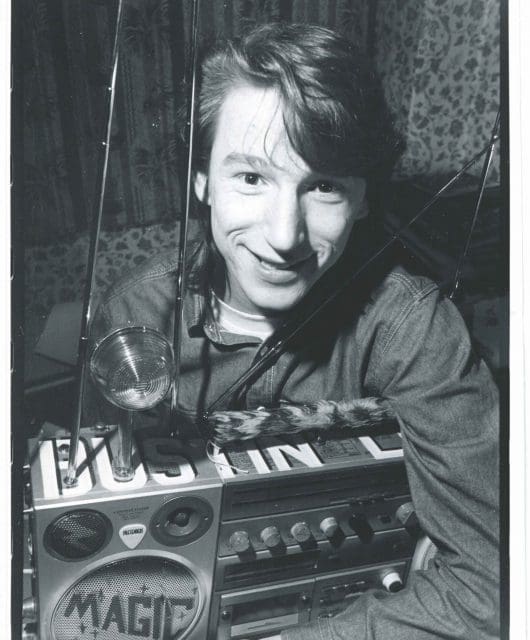

Eddy Grant interview: “Music is a great doctor”

By Steve O'Brien | December 14, 2023

A trailblazer since the mid-60s, Eddy Grant is one of pop’s great survivors. In this exclusive interview, the singer-songwriter reveals all about his near-fatal heart attack, taking on Donald Trump and how he’s been unafraid to make hits out of politically-charged subject matter…

At the dawn of the 70s, Eddy Grant, it seemed, had it all. There he was, a guy in his early twenties with a wife,

a couple of sprogs, and a victorious career as lead guitarist and songwriter of The Equals, most famous for their chart-conquering hit, Baby, Come Back.

He was almost the poster boy for clean living, proving that you didn’t have to be a drug-chasing libertine to be a pop star in the 60s. If there was an anti-Keith Richards at the time, it was Eddy Grant.

Heart attacks aren’t supposed to be on the agenda for teetotal, vegetarian, sports-loving twentysomethings, but on New Year’s Eve 1971 that’s exactly what happened to the man born Edmond Montague Grant when he found himself in intensive care, having suffered a massive coronary.

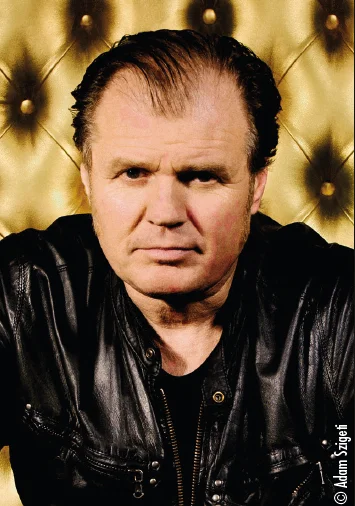

“Oh brother, it was brain shattering, heart shattering,” the now 75-year-old and fighting fit Eddy Grant tells Classic Pop, over Zoom from his home in Barbados. “It stopped me dead and made me look at my life in a different way.”

Little could he have known then, lying there in the ICU, that his greatest successes were still ahead of him.

He’d chalked up a trinity of Top 10 hits with The Equals: (1968’s aforementioned UK No.1 Baby, Come Back, 1969’s Viva Bobby Joe and 1970’s incendiary Black Skin Blue Eyed Boys, which was later covered by The Specials), but his biggest pop hits were still to come.

“When something goes wrong with your heart, you become this old man. Even walking to the bathroom is a pain,” he says, wincing at the memory. “Your whole set of circumstances change and you have to slow down. You have to think about everything very carefully before you act.”

Reluctantly, Eddy walked away from The Equals, the multi-racial rock-soul outfit he’d helped form in 1965 (“I tried to make an adjustment,” he says, “and the adjustment couldn’t be made within the context of the band”), taking 12 months off to let himself mend.

For the next few years he wrote songs, produced other artists (The Pyramids, Prince Buster) and set up his own recording studio at his home in Hackney.

In 1975, he finally released his debut solo album, the eponymous Eddy Grant. Except neither that, nor its fiery follow-up, 1977’s Message Man, caught the public’s eye.

Then, in 1979, Living On The Frontline happened. Its heavily politicised lyrics set against thick slabs of chart-friendly synth proved irresistible, propelling it to No.11 in the UK.

There were occasional chart wins over the coming years (1980’s Do You Feel My Love, 1981’s Can’t Get Enough Of You), but his following was largely confined to Africa and the Caribbean.

That all changed with I Don’t Wanna Dance and its parent LP, 1982’s genre-hopping Killer On The Rampage.

“It seemed like everybody knew something was happening with that record,” Grant says. Even his stonemason, a guy called Redman, sensed it was the big one.

“He said to me, ‘Boss, I don’t know much about music, but that record’s going to be No.1.’ And it was, it was a whacking great hit for me.”

ELECTRIC SHOCK

As seismic as I Don’t Wanna Dance was over here, it didn’t even break the Top 50 in the US. The song that made his name in the States was Killer On The Rampage’s follow-up, the crazily catchy Electric Avenue, which peaked at US No.2. But don’t mention that chart placing to Eddy.

“I’m a positive person, I don’t like to harp on about negative things,” he says, “but to me, No.2 is negative. I mean, it was No.1 on Cashbox.

“People keep harping on about it being No.2 on the Billboard, but at the same time, it was No.1 in Cashbox. So I, being the positive guy that I am, I say Electric Avenue was top of the charts in the United States of America.”

Forty years on, Grant admits that its success Stateside was bittersweet. While it was his first hit there (No.1 or No.2, you decide), DJs didn’t seem interested in spinning anything else with his name on it.

Forty years on, Grant admits that its success Stateside was bittersweet. While it was his first hit there (No.1 or No.2, you decide), DJs didn’t seem interested in spinning anything else with his name on it.

“It ostensibly stopped my progress in the United States,” he says regretfully. “Because remember, I Don’t Wanna Dance was No.1 all over the world.

“And so I’ve got this now to deliver and the guys won’t stop playing Electric Avenue, till today! I mean, I Don’t Wanna Dance, every child and every 90-year-old can sing it. Never got a chance in the United States… so far.”

For all of his music’s infectious danceability, those songs have a sharp political bite. But while there’s fire, there’s also positivity.

Just cock your ear to 1988’s anti-apartheid-inspired Gimme Hope Jo’anna, which, as well as raging against the white South African government, also remains optimistic that change is on the horizon – democracy finally came to the rainbow nation in 1994.

“I’m absolutely a believer that music can change lots of things,” he says. “What music can’t do is force people to change. It’s very difficult to bring about drastic social change, but you can create a greater sensibility and from that, little bits and pieces of social change can occur.

Gimme Hope Jo’anna tickles people’s imaginations that it’s possible to change. That song was popular amongst white South Africans as well, so here you’ve got a song that is decrying apartheid and the very people who are executing this apartheid love it.

“A song is a very powerful thing if the message is right, the beat is right, and so many other things. It’s not just words and it’s not just music, it’s a spiritual entity that floats around in the ether and every now and again it will land in some country and people will see its value.

“I mean, Gimme Hope Jo’anna was being played as the German National Football World Cup song! It became massive. Then Joe Allen came and got it for Wales. It’s universal.”

But if singles like Gimme Hope Jo’anna can be adopted by football clubs and sporting events (in 2017, The Sun modified its lyrics to support Brit tennis pro Johanna Konta at Wimbledon), his songs can also be appropriated by darker forces.

In 2020, Donald J Trump used the track – without permission, natch – on an anti-Biden advert. Grant then sued the former President for copyright infringement, seeking $300,000 in damages. Another legal headache for The Donald.

“The matter is subjugate,” he says cautiously, when we broach the subject. “But, yes, I did sue Donald Trump, and yes, it’s in the courts, but Donald Trump knows how to circumnavigate issues. It’s nothing personal. I don’t hate Donald Trump, I don’t hate anybody.”

FUELLING THE FIRE

Like Trump, though, Eddy Grant is another septuagenarian with fire in his belly, even if the targets of their ire are very different. In 2006, Grant released Reparation, an album which called for restitution for the transatlantic slave trade.

Asked what fuels his fury in 2023, it’s not just the dire state of the world, but the fact that few artists are as politically engaged as he and his contemporaries were 40 years ago.

“They don’t even write those kind of songs anymore,” he says. “It’s like writers have got writer’s block when it comes to socially conscious lyrics because they can’t get hits out of them.

“But I get hits with them all the time. I don’t write them because of fashion, or to get a hit. My brother said to me on so many occasions, ‘Why do you write those songs? The BBC won’t play them!’

“But I don’t write songs for the BBC. If they play them, fine, if they don’t, they don’t – some generation will find them, like how I found Johnny B Goode.

“Johnny B Goode wasn’t a hit in Guyana, it wasn’t a hit in Trinidad or Barbados, nothing. Nobody in this part of the world really knows Chuck Berry. But where he’s been needed, that’s where he is.”

And it’s fair to say that Britain needed Eddy Grant in the 80s, which is why the Camden Music Walk Of Fame recently honoured the Guyanese-born, Kentish Town-raised songwriter with a pavement plaque alongside other musical giants including UB40, The Sugarhill Gang, Buzzcocks, The Kinks and Shalamar.

“I lived there, I wrote there, I drove there, I became a man there,” he told us, a few weeks before the ceremony. “Why would I not want to be recognised in history? Because it’s all about history, it’s all about what you’ve done. When you leave this world, and I’m 75 years old now, it’s what you’ve done that counts, not who you are.

“Nobody in years to come will know Eddy Grant or Paul McCartney. Time erodes like the river erodes the bank. So yeah, there will be some general acknowledgement, but think about the billions of people that will come and go. As much as the stone will survive, I will survive.”

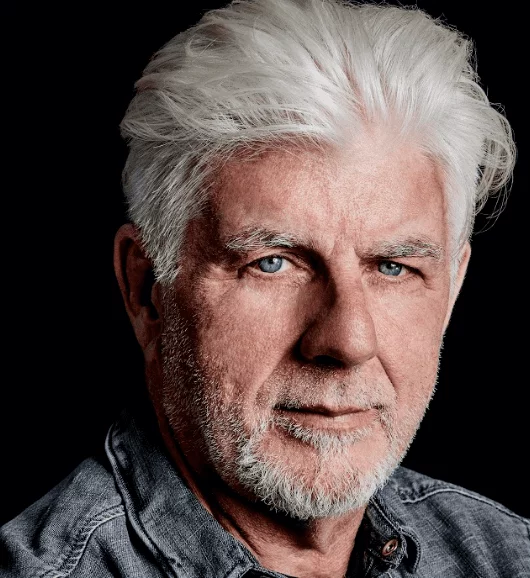

FACING THE FUTURE

There’s a sense in which an honour like the Camden Music Walk Of Fame is a punctuation mark that tells the world that an artist’s best work is behind them.

When some of us reach a certain age, death seems so much closer, but Eddy Grant first faced that fear 52 years ago and appears untroubled by thoughts of mortality.

“Whatever it is that God has for me in this world, he brings it to me,” he says matter-of-factly. “I don’t chase fame, I don’t chase money… these things come to me. And if it doesn’t come to me, then I reason that it’s not good for me.

“With that, I have a number of things that I do. I love old buildings so I spend a lot of time fixing my home. I do things in Guyana and in England – it helps to make some mark on the earth or in the air – and as I’m doing these things, the songs come.”

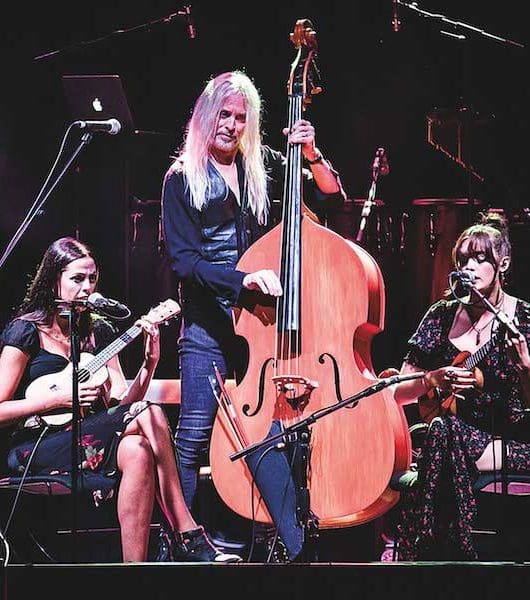

Grant’s next album is, he claims, in the can. It’s been six years since his last LP, the paean to his youth, Plaisance (named after the town where he was born in 1948), but he admits that his attention recently has been taken up with butting heads with Spotify and Apple Music.

Grant hasn’t allowed his albums onto any streaming services, describing the royalties paid to musicians as “rubbish”.

“In streaming,” he points out, “you have to do, I don’t know, 500 million downloads before you can get a week’s wage or something like that.”

Though album number 17 is done and dusted, the singer says he’s currently “waiting for the moment to launch it”.

Nearly 60 years into his career, Grant’s passion for the power of song burns as white-hot as it did at the very beginning.

Rewind six decades and, before the sounds of Chuck Berry stirred him to pick up a guitar, he’d planned to study medicine, so he “could do some good for people”. Surely, we suggest, he’s still ended up doing good for people, only as a musician, not a surgeon.

“Music is a great doctor,” he beams. “It’s probably a better doctor than the ones that go to university and study for seven years. Music cures, probably more things than the knife.”

It’s something heart attack survivor Eddy Grant knows only too well. Now 52 years on from his near-fatal coronary, he’s a living example of the healing power of pop.

- Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!

Steve O'Brien

Steve O’Brien is a writer who specialises in music, film and TV. He has written for magazines and websites such as SFX, The Guardian, Radio Times, Esquire, The New Statesman, Digital Spy, Empire, Yours Retro, The New Statesman and MusicRadar. He’s written books about Doctor Who and Buffy The Vampire Slayer and has even featured on a BBC4 documentary about Bergerac. Apart from his work on Classic Pop, he also edits CP’s sister magazine, Vintage Rock Presents.www.steveobrienwriter.com