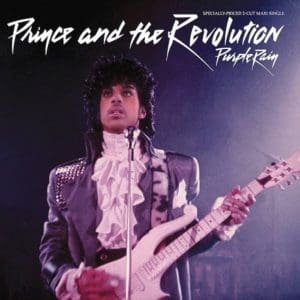

Prince – The making of Purple Rain

By Mark Lindores | February 6, 2024

The story behind Prince’s masterpiece Purple Rain

After years as the critic’s choice, Prince’s evolution to rock’s leading man saw him score a hit album, blockbuster movie and record-breaking tour. Backed by his greatest ever band, Purple Rain heralded his reign as rock royalty.

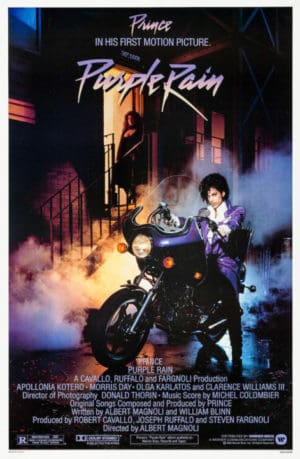

It was the night of 26 July 1984, and it seemed as if the entire world had descended on Hollywood Boulevard as scores of screaming fans, lines of Limos and satellite trucks aplenty thronged Mann’s Chinese Theatre for the world premiere of Prince’s movie debut, Purple Rain. In scenes more akin to the Oscars, stars including Eddie Murphy, Stevie Nicks, ‘Weird’ Al Yankovic and Lionel Richie walked the red carpet to witness the crowning of Tinseltown’s (and music’s) new leading man.

Naturally, the star of the show was last to arrive. Bedecked in his trademark purple and an air of his own self-importance, Prince, flanked by man-mountain bodyguard Charles Huntsberry, strode purposefully into the theatre denying the assembled hordes eye contact or even acknowledgement. What the diminutive star lacked in stature, he made up for in sheer star quality. Baby, I’m A Star, he sang in the film and boy, did he believe it.

Baby I’m A Star

Although there is no doubt that Purple Rain elevated Prince to the pantheon of pop icons, he was already well on his way to becoming a superstar. He’d been a darling of the critics ever since his debut album For You in 1978 and the release of 1999 gave him the mainstream breakthrough he’d slavishly strived for.

As well as producing an album a year, the prolific star had been writing and producing for a string of protégés and touring consistently, playing for audiences ranging from nine people in a dive bar to 90,000 irate Rolling Stones fans who’d booed him off the stage less than three years earlier.

The success of 1999 had put Prince in a powerful position when his contract with Warner Bros was due for renewal upon delivery of his fifth album – and he knew it. “He said he’d only sign with us if he got a major motion picture,” Prince’s former manager Bob Cavallo told Spin. “It had to be with a studio and his name had to be above the title. Then he’d re-sign with us. He wasn’t even a giant star yet! I mean, that demand was a little over the top. Everybody turned us down.”

Meeting resistance at every turn, Cavallo agreed to co-produce the film himself with Warner Bros funding and distributing it.

Arrogance Or Ambition

The fact that no studios were willing to finance what looked on paper to be an artist’s vanity project is hardly surprising. Despite having scored two big hits with 1999 and Little Red Corvette, Prince was still very much regarded as a niche artist and people were still unsure what to make of this elusive, awkward androgyne whose work was steeped in sex and religion.

Whether it was arrogance or ambition, Prince’s faith in the film becoming a success was unwavering. He’d told friends as far back as 1981 of his desire to make a semi-autobiographical movie. It was an opportunity for the enigmatic star to establish a relationship with his audience and control the narrative of what he wanted the world to know about him.

During 1983’s Triple Threat Tour, he was constantly in possession of a large purple notebook in which he was forever writing. What everyone presumed were song lyrics, also included script excerpts and scenarios for the film.

Children Of The Revolution

Director Albert Magnoli signed on to helm the film and rewrite the script (original writer William Blinn’s script entitled Dreams was deemed too dark), immersing himself in the Minneapolis music scene to gain true insight into its machinations and its characters.

Feeling it would be inauthentic to try and replicate it for filming purposes, First Avenue, the mecca of the city’s live scene, was closed for six weeks for filming with many of its patrons serving as extras (post-Purple Rain, the club would become to Minneapolis what the Cavern Club is to Liverpool).

Now officially known as The Revolution, the band were sent to acting and dance classes, much to their bemusement, to learn the basics of acting. Prince protégés The Time were cast as his rivals and girlfriend Vanity would be playing his on-screen love interest (Vanity left the project prior to shooting and was replaced by Apollonia Kotero). When Magnoli questioned Prince about music, he was told that over 100 songs were written and was invited to listen to them so they could decide which would work in the context of the film.

Musical Equals

Although Prince had always been notoriously prolific, the formation of his new musical family had given him new fervour. The Revolution was his evolution. If he were to achieve his goal being a stadium-sized rock star, his music needed to be fleshed out with more bombast. His previous work, while brilliant, had been very insular given his propensity to write, produce, arrange and perform everything alone.

Recognising the talent and potential of the tight collective he’d amassed – Matt ‘Doctor’ Fink on synths, Brown Mark on bass, Bobby ‘Z’ Rivkin on drums, Eric Leeds on sax, guitarist Wendy Melvoin and keyboardist Lisa Coleman, he opened himself up to accepting input from them, particularly Wendy and Lisa (art would imitate life when this new-found democracy was written into a plotline in the film).

“We were absolute musical equals in the sense that Prince respected us and allowed us to contribute to the music without any interference,” Wendy told Mojo in 1997. “I think the secret to our working relationship was that we were very non-possessive about our ideas, as opposed to some other people that have worked with him. We didn’t hoard stuff and we were more than willing to give him what he needed. Men are very competitive, so if somebody came up with a melody line, they would want credit for it.”

The Colour Purple

Not only did Wendy and Lisa have input into the music, they also turned Prince on to styles and genres he’d never paid close attention to before. Modern classical composers such as Vaughan Williams, Stravinsky, Ravel and Scarlatti were a revelation to him and flourishes and fills began creeping into his work henceforth. Its influence can be heard in the strings of Take Me With U and the baroque-inspired keyboard bars of When Doves Cry (not to mention the sonic detours of subsequent albums Around The World In A Day and Parade).

Because work on the album and the film was taking place concurrently and Prince was overseeing everything, a warehouse in St Louis Park on the outskirts of Minneapolis served as Purple Rain HQ. Fitted with soundstages, studios and offices, it meant everyone could convene in one space and Prince could easily jump from a script meeting to band practice to the studio with ease (it also gave him the idea to build his own Paisley Park complex later). The space also meant that creativity could flow freely without interruption.

At the end of one particularly long day of rehearsal, Prince asked the band to quickly run through something he’d been working on as the project’s potential title track. He’d had the country-inspired song for a while and had sent it to Stevie Nicks to write lyrics to. She had politely declined, explaining that she found the 10-minute-plus instrumental beautiful but too intimidating. As Prince played the song, roughly outlining the verses, the band began adding chords, switching the arrangement round, harmonising… Six hours later, Purple Rain was almost complete.

Powerful Punch

That spontaneity was an example of how Prince and The Revolution typically worked. Although very much collaborative – both onstage and in the studio, Prince was always the bandleader. They developed a shorthand whilst playing, with a simple look or gesture from him determining a switch in pace or direction – the band was that tight.

Rehearsals would often stretch into the early hours. These prolonged jam sessions were how much of the album came to be. The expansive warehouse space played a huge role in delivering the powerful punch of Let’s Go Crazy.

Likewise, Computer Blue. When Prince made the decision to make the soundtrack solely a succinct Prince and The Revolution album, not only were the tracks from The Time and Apollonia 6 omitted, so were some of his own, including God and Father’s Song. The former was released as the title track’s B-side and the latter was reworked into a guitar solo for Computer Blue (both were later included on the Deluxe Edition of the album in 2017).

Going Live

Outside of the Revolution material, Prince was working on music for The Time and Apollonia 6 and wrote and recorded a pair of solo tracks. The Beautiful Ones, one of his greatest ever ballads, and Darling Nikki, a sexually explicit track which evoked his earlier work.

Once the music was written, the group rehearsed it over and over on the warehouse stage, refining it until it was ready to be performed in public. It was common practice for Prince to gauge an audience’s reaction to a song to determine its fate.

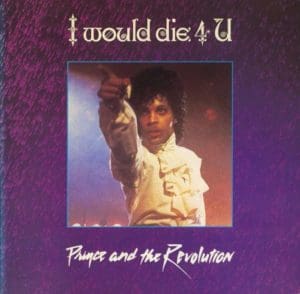

On 3 August 1983, the band held a benefit concert for the Minnesota Dance Theater at First Avenue. With the exception of some minor overdubs, the live performances of I Would Die 4 U, Baby, I’m A Star and Purple Rain feature on the album in their raw state.

Shot in just six weeks in November 1983, in Minneapolis and Los Angeles, Purple Rain incorporated elements from Prince’s own life, dealing with issues such as insecurity, jealousy, band rivalries, a strained father/son relationship and striving for success.

MTV Generation

The first movie of the MTV generation, the narrative is spliced with scintillating live performances. Albert Magnoli wanted the live footage to be as dynamic as possible so that the performances could stand alone as videos on MTV if needed and had set aside four weeks to film them.

Prince assured the director that amount of time wouldn’t be needed and, true to his word, the performance scenes were completed in less than a week, including re-takes for different camera angles. “We had been rehearsing those songs live for six months, we knew what we were doing,” Wendy Melvoin laughed.

Just as the film was nearing completion, Magnoli asked Prince for one more song to use over a montage showing the complexities of the different relationships The Kid (Prince’s character) has with his band, his parents, his lover, his rivals and himself. Prince delivered the sparse masterpiece When Doves Cry the following day.

A last-minute inclusion on the soundtrack, it was released as the first single in May 1984 and became Prince’s first US No.1 single, topping the Billboard chart for five weeks. The Purple Rain album was released to critical acclaim a month later and had sold 2.5 million copies by the time the film premiered on 27 July. The following week, it hit the top spot, where it stayed for 24 consecutive weeks and produced further hits in Let’s Go Crazy, Purple Rain, I Would Die 4 U and Take Me With U.

Box Office Smash

While the film received lukewarm reviews from the critics, audiences couldn’t get enough, and Purple Rain knocked Ghostbusters off the top spot at the box office. In September 1984, with Let’s Go Crazy at No.1, Prince became the third act in history to top the singles, album and film chart simultaneously, following Elvis and The Beatles.

Shot with a budget of just $7 million, the film’s box office takings exceeded $70 million and it was the ninth biggest film in the US in 1984. Meanwhile, the album went on to become one of the biggest soundtracks of all time, with over 25 million copies sold to date and earned Prince an Academy Award for Best Original Song Score for Purple Rain.

The newly crowned megastar capped his most successful year by kicking off the Purple Rain Tour in November. Every date sold out in minutes, leading to additional shows constantly added to meet demand. However, although he lined up studio time for whichever city he was in, Prince felt creatively stifled at having to play the same set every night. He was already hard at work on two albums and another movie.

Plans to take the tour overseas were shelved and the tour ended in April 1985, having played 98 shows to over one million people. For those unable to score tickets and international fans, the show in Syracuse was filmed (now regarded as one of his greatest performances) for broadcast on TV internationally and released on home video. The Revolution it seemed, would be televised after all.

Purple Rain Track By Track

LET’S GO CRAZY

The sermon-like, “Dearly beloved, we are gathered here today to get through this thing called life” gives way to a frenetic dance beat, reminiscent of Delirious from 1999, before a screaming guitar instructs the listener to “go crazy”. The song’s meaning has been heavily debated over the years, and Prince has said that due to radio restrictions on mentioning religion, he had to find other ways of relaying his message and this was one of those instances. The song gave him his second US No.1 hit and was his staple concert opener since its release.

TAKE ME WITH U

Prince wrote this to the specification of Purple Rain director Albert Magnoli, who wanted a breezy, upbeat track to counteract the film’s darker moments. It was recorded as a duet with Apollonia Kotero, Prince’s on-screen love interest. While Kotero was great in the film, she wasn’t an experienced singer, so Lisa Coleman was brought in to contribute to the track to even out the vocals.

THE BEAUTIFUL ONES

The Beautiful Ones was a late addition to Purple Rain, replacing a song called Electric Intercourse. Written and performed entirely by Prince, it was inspired by his feelings for Susannah Melvoin (his bandmate Wendy’s twin sister). A haunting tale of unrequited love, the track is built on a simple drum machine and keyboard track. Prince’s vocal delivery is what cements the emotional intensity. Almost whispering at the beginning, he’s screaming by the time

the song reaches its crescendo. It soundtracks a pivotal moment in the film, as Prince attempts to steal Apollonia from his rival, Morris Day.

COMPUTER BLUE

One of the most-asked questions about Purple Rain is: what is the meaning behind Lisa Coleman and Wendy Melvoin’s “Is the water warm enough?” intro? “We had no idea,” says Wendy. “Prince gave us a piece of paper and asked us to say it. We had no idea it had weird psychosexual connotations.” Originally over 14 minutes long, the track was edited down to enable Take Me With U to fit on the album. Prince’s father, John L Nelson, is credited as co-writer on Computer Blue, as it incorporates Father’s Song, a track he gave Prince to use in the film.

DARLING NIKKI

The most controversial track on the album, due to its opening line, “I knew a girl called Nikki/ I guess you could say she was a sex fiend/ I met her in a hotel lobby, masturbating with a magazine”, Darling Nikki was singled out by Tipper Gore and the Parents Music Resource Center, and prompted the introduction of Parental Advisory/Explicit Content stickers for albums containing sexual or violent content. Another solo Prince composition, Darling Nikki has been covered by artists including Rihanna and Foo Fighters.

WHEN DOVES CRY

When Prince was recording When Doves Cry, the final track for the album, legend has it that he said to the sound engineer, “Nobody would have the balls to do this. People are going to freak.” He was referring to the fact that the song had no bassline. The minimalist track is a complex story of the relationships Prince’s character in Purple Rain, The Kid, has with his girlfriend and parents. One of those songs that shouldn’t work, it still stands as one of Prince’s greatest-ever releases.

I WOULD DIE 4 U

On first listen, I Would Die 4 U is a straight-up love song, with Prince declaring his feelings over shimmering synths and a dance beat. The opening line of, “I’m not a woman, I’m not a man, I’m something that you’ll never understand” harks back to his Controversy era. But when investigated further, it’s apparent that Prince is singing from the viewpoint of Jesus, and this was confirmed on the Purple Rain Tour, when he changed the lyric from, “I’m your messiah and you’re the reason why” to “He’s your messiah”, while pointing skywards.

BABY I’M A STAR

Originally written in 1982 during the prolific 1999 sessions, Baby I’m A Star perfectly encapsulates the Prince live experience (it was recorded during his band’s infamous First Avenue gig in August 1983). The prophetic lyrics, “Baby I’m a star/ Might not know it now, baby, but I are/ I’m a star/ I don’t wanna stop ‘til I reach the top,” suggest that Prince was confident he was going to achieve huge success, and he kept the song back until he felt the time was right to release it.

PURPLE RAIN

The definition of the word ‘epic’, the album’s title track was a soaring, anthemic rock ballad written by Prince with Wendy Melvoin, originally for Stevie Nicks. “Prince had the idea and the melody, then I added chords and a guitar part, and the rest was everyone else chipping in,” says Melvoin. The nine-minute-long track provokes discussion to this day, with fans debating hidden meanings in the lyrics, revelling in the mysticism that Prince often threaded through the tapestry of his work.

Buy our Classic Pop Presents special edition devoted to Prince here

Read Classic Pop’s top 10 Prince songs