Long seen as the club that invented Britain’s cultural life in the 80s, Blitz was the epicentre of both music and fashion. So why was it created at a dodgy World War II−themed wine bar? Blitz DJ Rusty Egan, Boy George, Gary Kemp, Midge Ure, Philip Sallon and Sue Scadding delve into the madness of the iconic club that spawned the new romantic movement.

The 1980s were invented at the Blitz. Or so the popular image of one of Britain’s most outrageous, certainly outré, clubs in our cultural history would suggest. The New Romantic movement definitely started with Rusty Egan and Steve Strange’s hangout.

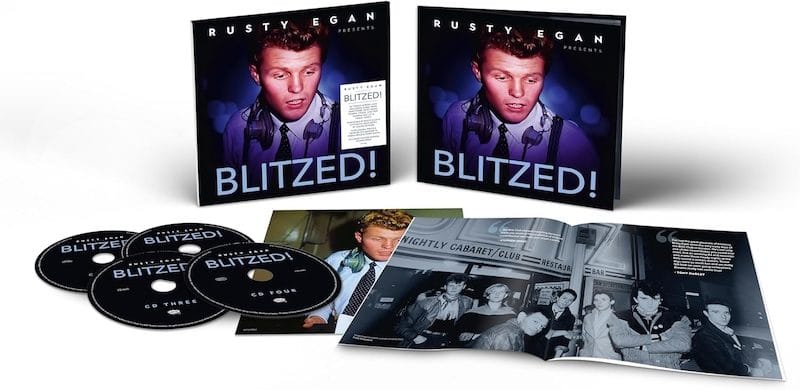

It’s taken a startlingly long time to celebrate it, but Rusty is now showcasing the music that started a revolution on a boxset, Rusty Egan Presents BLITZED!. However, the eclectic mix of glam, European electronic art, Krautrock, goth and, yes, a few synth-pop bangers shows how wide-ranging the Visage drummer was behind the decks. It also proves just how short-lived Blitz was in blowing people’s minds. By the start of 1981, Blitz was done.

The Real Blitz

Rusty’s pleased to finally celebrate his legacy – and to hopefully shut people up about what he didn’t play. An ebullient, hyperactive talker, he admits: “Every day, people come up to me saying: ‘Hey Rusty, when are you doing a compilation?’ It’s a relief to get one out, after a lot of effort to get the rights. People who ask about a compilation then tell me: ‘Why don’t you put Don’t You Want Me and Tainted Love on there?’ Because they weren’t released when the Blitz was happening! Blitz was 1979-80. This isn’t Now That’s What I Call The Fucking 80s, it’s the real Blitz.”

If Rusty is occasionally frustrated at the myths around what he helped create, Gary Kemp is delighted one of Spandau Ballet’s biggest influences is finally being celebrated. “I wasn’t a ‘fan’ of Rusty as a DJ when I was going to the Blitz,” he considers. “It wasn’t that kind of fan relationship, because everyone going to the Blitz felt like we were a team. Of course, in hindsight I now know Rusty was so important.”

Future Of Music

Boy George was another admirer of what soundtracked his time working in Blitz’s cloakroom, enthusing: “I always found nightclubs ridiculous, but I loved dancing. Credit to Rusty, he always had great taste. So many of those songs had me running to the dancefloor dressed as a nun, with my Boudicca helmet falling from my head. I was drunk and in love with everyone, but most in love with Fad Gadget – the unsung king of electronic music.

“I think growing up in the 70s, we all just loved everything – pop, glam, rock, reggae, electronic, even classical. If Steve and Rusty were coppers, Rusty would be the nice cop. Steve was often on a power trip and loved turning people away. He loved lording it on the door. He turned away Mick Jagger, which I was appalled by. Going to the Blitz was always exciting – a drunken backcombed bitch fest. Steve never turned Philip Sallon away, though. Ever. He wouldn’t dare. Philip was the mother of all freaks. Still is really.”

George’s vivid portrait of his typical look for the Blitz highlights the club’s other storied legacy. What Rusty Egan was doing for showing the future of music, Steve Strange was ushering in for fashion. Having fled his native Caerphilly to become a punk in London, Steve’s extravagance and attitude were more suited to ensuring the future would be as colourful as possible. “Steve and Rusty couldn’t be more different,” accepts Kemp. “Yet together, they seemed to represent who the crowd in Blitz were: straight, gay, working-class, middle-class, outrageous, inventive. There was such a great mix under that roof.”

A New Movement

Rejecting punk’s uptight musical conservatism was inevitable, according to Midge Ure. He was coping with the fallout from his band Rich Kids, which featured Rusty on drums alongside guitarist Steve New and former Sex Pistol Glen Matlock on bass. Famously, the band split when Midge bought a Yamaha CS80 synthesizer. Rusty was delighted; Glen and Steve much less so. Punk, they insisted, was about guitars. “In 1979, a lot of what was happening was the dying dregs of punk,” Midge explains. “The kids who went to Blitz had been through all that and wanted something new, something else. And the punks themselves were fed up. They wanted to move on, because once your younger brother starts to like something, you don’t want to anymore.”

That was certainly true of Philip Sallon. One of the original punk instigators as part of the scene’s equivalent of New Romantic, the Bromley Contingent, whose number included Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood, the future club promoter could sense that something new was about to take its place. “Whatever’s next is going to happen, and who wants to be there after the event? I’d rather be there before the event,” Sallon laughs. “Punk wasn’t ‘Let’s be the next scene,’ but they were still verging on being fashion victims. What those movements were about was being ahead. The Bromley Contingent and Blitz Kids both wanted to be part of what was about to happen.”

Towards the end of 1978, Strange and Egan started their first night at Billy’s in Soho. It was an immediate success, but they quit after three months when the promoter doubled the price of the drinks. “Billy’s owner told us: ‘You’re onto a goldmine here, lads,’ but we told him that wasn’t why we were there. It was about the music, never about becoming a business.”

Are ‘Friends’ Electric?

Steve’s day job was at PX, a clothes shop whose outfits would become key to New Romantic. PX’s owner, Helen Robinson, recommended he and Rusty instead try hosting a night at Blitz, a World War II-themed wine bar in nearby Covent Garden.

“Blitz was basically ’Allo ’Allo,” chuckles Egan. “It was a hokey French-style place, down to candles in wine bottles. All it had going for it was you could smoke in there.” Gary Kemp adds: “There were World War II posters everywhere. Did that represent Blitz Kids? Kind of, maybe, because it gave it a little bit of a setting for our dressing-up box. But Steve and Rusty only had it for one night a week, and that was Tuesdays, which, of course, isn’t usually a great night for takings in a club. Then Rusty and Steve took it over and made it part of history. The other four nights a week, Blitz was just a regular wine bar.” Gary’s voice drips with disdain. “Really naff people probably went there then.”

One of Billy’s regulars, Sue Scadding, was coincidentally a barmaid at Blitz. She recalls: “Blitz’s manager, Brendan Connolly, told me Steve and Rusty had asked if they could do a night at Blitz. Brendan asked me what their night at Billy’s was like. I told him it was fantastic, and Brendan said: ‘OK, let’s do it, then.’ Everyone was so young at Blitz. Brendan was only 24 himself, and even Mike Brown, the owner, was 26.”

Got The Look

Egan had befriended Strange after being impressed by his eyeliner ‘n’ peroxide look, introducing himself to the Welshman after spotting him in the street. Steve eventually crashed on Rusty’s sofa and hung out with Rich Kids on tour.

Before starting at Billy’s, Steve also began taking Rusty to gay clubs. “They’d play sexy music by sexy people,” says Rusty. “Soul music was sexy at that time, too: Chaka Khan, Sexual Healing. But next to that, I was listening to music I was buying when I went to Berlin and Düsseldorf. Kraftwerk were telling you what Platform 9 was like at Düsseldorf train station. They weren’t trying to be sexy at all.”

Nonetheless, Egan thought it would be relatively easy to make it all fit to soundtrack a glamorous night out, insisting: “I didn’t think being a DJ would require much talent. You picked the right tunes, put them on at the right time and made sure you didn’t drop a beat. I was a drummer, so how was I going to miss a beat?”

Club Curation

Of course, Steve Strange wasn’t going to let just anyone in to experience Rusty Egan soundtracking the future. “Steve was a great curator of people,” notes Gary Kemp. “Every great club needs someone curating who gets in: the psychedelic scene at UFO club had Joe Boyd and Hoppy Hopkins, the glam club Middle Earth had Jeff Dexter. Blitz had to happen. We were the next generation after punk and we knew we were about to have the spotlight thrown on us. We had to show what we were about, what we were going to do. Blitz felt like a duty.”

It was no coincidence that Blitz started in 1979, according to Kemp: “We felt a responsibility that we were going to define the youth culture of the 1980s. The fact that it was going to be 1980 soon, that was an impulse.”

Despite being bored of punk, Midge Ure agrees with Philip Sallon that there were similarities. Midge points out: “Kids were rebelling against what a dark, dingy miserable time it was in the UK. The way we dressed at Blitz was as punk as picking up a guitar when you didn’t know what to do with it. This was the punk ethos in a different direction: dress up, look overtly glamorous and listen to people hitting synthesizers with one finger. It was the same thought process as punk, just done with some glitter on it.”

Make An Effort

To get past Steve Strange, you had to make an effort. It helped in being able to dress up that Britain’s most famous fashion college, St Martin’s School Of Art, was a few minutes’ walk from Blitz. John Galliano, Willie Brown, Melissa Caplan, Stephen Jones and Stephen Linard are among the designers who were Blitz regulars. “The moment you can’t get in somewhere, there’s a mystique about it,” notes Ure. “Some people could afford to shop at PX, but not many of us. I wore what I could afford: demob outfits and double-breasted suits from Oxfam. You had to be creative and inventive. It’s actually what I wore in Ultravox, too.”

“We were glam rockers who became punks and then took it further,” according to Boy George. “We threw in a bit of goth for good measure. We loved Cabaret and John Waters’ movies with Divine. We lived for the subculture and we were the subculture.”

Even someone as dressed to impress as George wasn’t always convinced he’d have Steve Strange’s approval. “I was always at war on and off with Steve,” he confesses. “Obviously, I loved Steve, but we were immature and fell out all the time, mostly about clothes and hairstyles, who did it first. Occasionally, it was over boys. So I wasn’t completely sure if Steve would turn me away or not.”

Of his first time at Blitz, George remembers: “It was good news I got in, because I turned it on visually that night. I wasn’t dressed for being sent home.”

Not everyone thought a door policy so strict that Mick Jagger famously got turned away was a good idea. Philip Sallon states: “Blitz had a VIP room, before virtually any club did. Steve was picking up on the right-wing inequality introduced once Mrs Thatcher came to power. Blitz was all about inequality. You had to be above everyone else to get in there but, once you were in, many people were still above you. Steve was great at picking up on those unequal vibes.”

A Safe Haven

However, Boy George believes Blitz was a haven for anyone with an alternative lifestyle, noting; “People were very relaxed about sexuality at Blitz, where being queer was a great calling card. Gays, especially the loud variety, were still a novelty in the 70s. Gay clubs were full of gay clones, wearing biker leathers and lumberjack shirts with jeans. Blitz was a refuge from judgement, both by conventional queens and casuals.

“I feel the Blitz carried on the work of every freak that ever walked the earth. Alternative people – not just queers and lesbians, but anyone who felt like an outsider. I know there has always been a subculture and we gravitated towards the underground. These days we celebrate and almost enforce diversity. Diversity comes with a ton of new labels. People are not interesting because of their sexuality but because of their character. Clothes can tell a different story to the world, but in the end we were all some mother’s kid in make-up. When Bowie sang ‘Oh you pretty things’ we felt like he was pointing at us. Rusty is straight but he was a dandy back in the day. He turned out in full Biggles…”

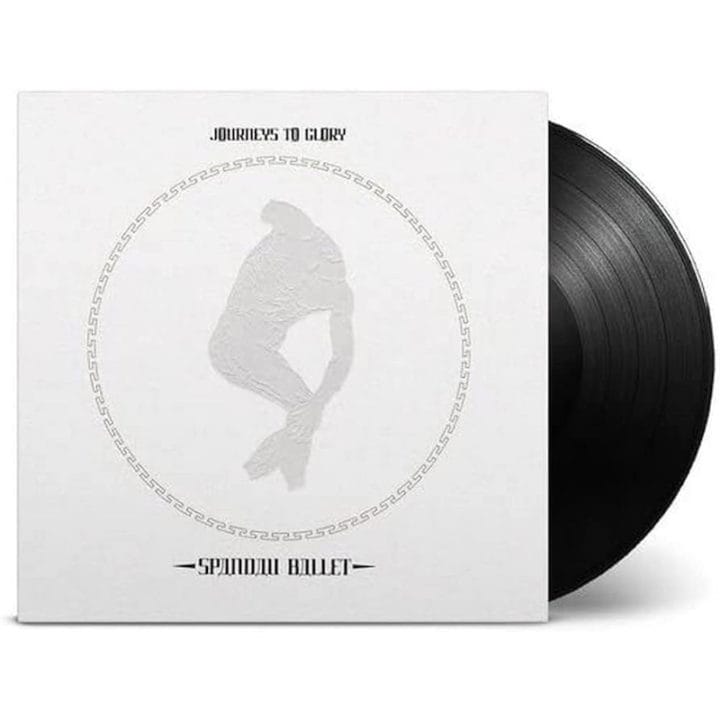

In that maelstrom, any house band would need to look and sound spectacular. Enter Spandau Ballet. “Before I went to Billy’s for the first time, I’d kind-of given up,” admits Gary Kemp. “We were called The Gentry. We were playing mod, but wearing soul boy clothes. We fell between every stool and it really wasn’t going to happen for us. Then, when I went to Billy’s with our manager Steve Dagger, I realised: ‘We need to buy a synthesizer.’ We all chipped in to buy one and I rewrote everything, based on what I heard coming from Rusty’s DJ booth. That music was the inspiration for Spandau’s first album.”

House Band

House Band

As well as soaking up the music, Spandau were enthralled by the licence to dress up. “Steve Strange was smitten with Spandau,” smiles Rusty Egan. “They were fresh-faced, beautiful boys. Steve said: ‘Give them whatever they want,’ but I did the schoolteacher thing on them, giving them a lecture: ‘You don’t need a drummer or guitarist. What guitar can you hear in what I’m playing? OK, there’s Adrian Belew on David Bowie, but are any of you as good as Adrian? I doubt it.’ I made them work for it, and introduced them to their producer, Richard James Burgess. They just needed a producer who knew what he was doing.”

Spandau’s first ever gig was at Blitz’s Christmas party in 1979. “It was utter nerves,” admits Gary. “We knew it was do or die. We couldn’t believe it when people were looking at us, because at Blitz people were only interested in performing themselves, in how they danced. If they hadn’t liked us, that was it. But they did – so that meant my brother was staying in the group.”

Among the audience was Sue Scadding, who remembers: “It was obvious even at the time there was a lot of talent at Blitz. Spandau’s first performance was amazing. It was a trial run before Steve Dagger would let them play anywhere else, and they were fantastic.”

Rich Tapestry

While Spandau were on Top Of The Pops within a year with To Cut A Long Story Short, Egan and Ure were plotting their next band to follow Rich Kids. “Rusty was always a driven, powerhouse of energy,” says Midge. “When he wasn’t banging drums at a million miles an hour, he’d talk at a million miles an hour. I’d listen to his mad ramblings, one of which was: ‘Wouldn’t it be great to get a band together to make the music we like, using all our favourite musicians?’ And that was Visage. Out of Rusty’s millions of outpourings, I jumped on that one.”

They still had demo time owed to them by EMI from Rich Kids, so the pair recorded a cover of Zager And Evans’ In The Year 2525 and a demo of future Visage favourite The Dancer. “We could have gone anywhere,” reasons Ure. “We were on our own, with no template. We just had a synthesizer and a drumkit, but that was the nucleus of what we wanted. It was incredibly basic – one-finger keyboard stuff, a maximum of three fingers. But we made it work.”

Their favourite musicians were soon recruited: John McGeoch, Barry Adamson, Dave Formula and Midge’s new Ultravox bandmate Billy Currie. Having joined Ultravox, Midge didn’t fancy fronting two bands. Why not get Steve Strange in? “Steve wasn’t a natural singer at all – but he was great at everything else,” emphasises Midge. “The look was a major part of it all. He brought the bravado, the look and the great creators who were part of Blitz: the photographers, video-makers, designers. I’d sing the song to Steve, so he’d have my voice in his head while he followed the melodies.”

Glitz & Glamour

While Visage were getting together, Rusty was enjoying blowing people’s minds every Tuesday, behind Blitz’s very primitive decks. “In those days, you couldn’t change the tempo,” he explains. “There was no fader, so you had to use your finger on the decks’ grippy bit to fade a song out. Slipmats only came out later. Technically, it was a little difficult, but you’d get the general idea across.”

Rusty was well aware of the symbiosis between music and fashion that he was introducing: “Blitz took you out of the grim and horrible Thatcherite Britain, with piles of shit on your doorstep. You had no future and nothing glamorous was happening? Forget that, I’m going to get dressed up, so I can forget about my crap on the dancefloor. And if I’m on the dancefloor looking fantastic, I don’t want to hear Boogie Oogie Oogie.”

Alongside Kraftwerk, La Düsseldorf, Nina Hagen and Gina X Performance from his trips to Germany, Rusty would play French chanson music, revealing: “I was an old romantic. I loved French films, Paris and film noir. The music in Death In Venice killed me. What was more interesting than feeling like you’re in a club in Paris, listening to Space or Jean-Michel Jarre or Jacques Brel? We needed a bit of glamour.”

Visiting Royalty

Eventually, Blitz was given the ultimate seal of approval when, in July 1980, David Bowie came to see what all the fuss was about. “When David Bowie walked in, everyone was screaming ‘Bowie! Bowie!,” sighs Philip Sallon. “They were putting their hands in the air to try to get to him. I thought it was disgusting. The overriding message of Blitz was that it was about stardom. Idol worshipping is not my thing, because no one is better than anyone else.”

Not everyone was so starstruck. “I snubbed him,” grimaces Gary Kemp. “I’m as big a Bowie fan as anyone can be, but I was in a band and thinking: ‘No, we’re the next generation.’ Everyone was so excited when Bowie came in, it annoyed me. He went upstairs, so I stayed downstairs, trying to ignore him – when in my heart, it was like the Pope had come in. Bowie arriving was the blessing that Blitz needed to confirm it was the place to be.”

Bowie was also on the lookout for Blitz Kids to star in his Ashes To Ashes video. Steve Strange naturally appeared, helping Bowie to choose regulars Judith Franklin, Elise Brazier and Darla Jane Gilroy to star in the David Mallett-directed promo. They each earned £50 for helping Bowie to kickstart his 1980s.

Something Special

While Boy George admits he didn’t make the grade for the video from his own disappointing first meeting with Bowie, he was clearly destined for stardom with or without his hero. George’s workmate Sue Scadding recalls: “George was always hilarious. He was outrageous. Working with him, I’d think: ‘Oh no, now what?’ You knew he was great, but I didn’t think his singing would be that good. How can you know that when you work with someone? When I first saw Culture Club live, I thought: ‘I never knew you could do that.’”

Bowie’s blessing proved to be the ultimate Blitz moment. By the time the club closed in September 1981, most of its main faces had drifted away. Owner Mike Brown sold it to a restaurant owner who turned it into an American canteen.

By then, Sallon had opened the legendary Mud Club, Strange started goth joint Hell, Egan opened Camden Palace – where he put on the debut British gig by Madonna and the first London show by Frankie Goes To Hollywood. The club is still thriving now, as Koko.

“We realised when we were there that Blitz was something special,” insists Gary Kemp. “When you left, there’d be cameras from Japanese film crews outside.” Boy George has similar memories: “Some photographer or other was always taking pictures and we lived for the pose.”

The Other Bloke…

Blitz’s impact was brought home to Sue Scadding when she bumped into Tony Hadley at a recent TV show. She laughs: “I was wearing John Galliano jeans. Tony gave them a tug and said: ‘My God, not another Blitz person!’ It was so funny – a lot came out of Blitz.”

“Clubs are very different now,” considers Philip Sallon, who remains a tireless innovator in London nightlife. “The music at Blitz was tremendously loud. It was a reason to be there. Now, the music is a bit secondary. Clubs are much more about networking.”

Even at a time when Midge Ure was in Ultravox, Visage and Thin Lizzy, Blitz matched them for excitement. “Going from the dying embers of Rich Kids to seeing everything explode within a year was so fortuitous,” he accepts. “For a while, I was riding on the crest of a wave, the guy helping to steer it behind the scenes. It’s short-lived, but for that moment you think: ‘OK, something is happening here.’”

As for the man who helped start it all? “I don’t think Blitz invented the 80s,” ponders Rusty Egan. “That was Margaret Thatcher. She was the one who created Del Boy with his Filofax. What I did was to put together a soundtrack, where everything fell into place.”

He’s overdue some mainstream recognition, is Rusty, still a force as a DJ and remixer. “I’m not as good a songwriter or performer as Midge,” he counters. “Then again, there’s often the other bloke: the other bloke in Soft Cell, the other bloke in Pet Shop Boys. Me? I’m the other bloke.”

To buy Rusty Egan Presents BLITZED! click here

Read More: Top 40 New Romantic songs

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.

House Band

House Band