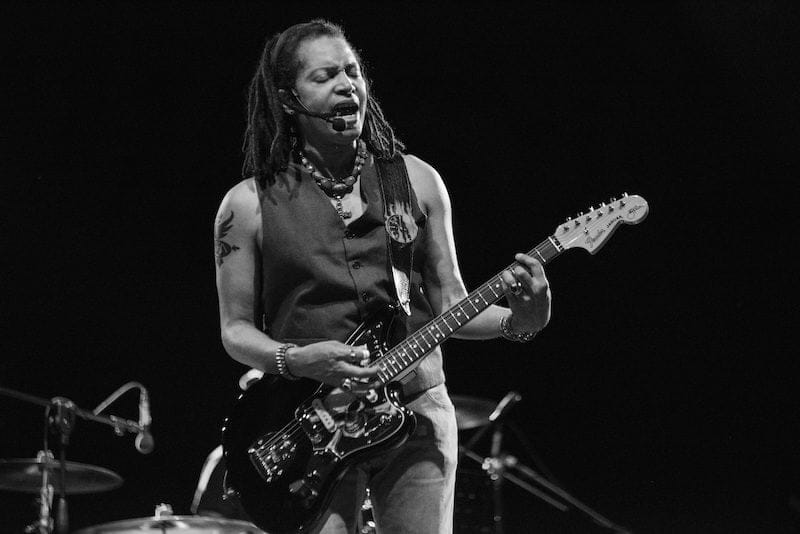

Image credit: Manuel Scrima

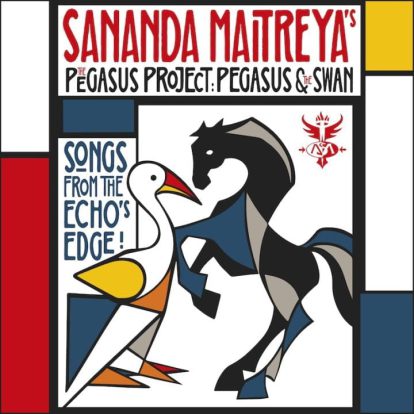

In this Classic Pop Sananda Maitreya interview, the singer discusses his 13th album The Pegasus Project: Pegasus & The Swan and reveals why Britain is an emotionally troubled place to visit, how kids’ TV has influenced his own work and why he’s repulsed by trumpet players…

Music has a long history of being influenced by singers becoming parents. Sananda Maitreya might not have written any direct odes to his two sons, 13-year-old Francesco and Federico, 11, but fatherhood has reminded Maitreya of a valuable lesson about songwriting.

“When my sons were born, I was confronted by baby TV every day,” says Sananda from his home in Milan, where he’s lived since meeting his wife, Francesca, at the start of the century. “One of the first things I noticed about those children’s shows is their background music is pretty sophisticated. The music is simple, but their arrangements are clever. It helped me recalibrate to the genius of simplicity, of music in its purest form.”

For a singer who grew up wanting to be “the charming, elegant guy who had a Shakespearean turn of phrase and could make the ladies swoon”, the power of words has been important to Maitreya since his debut album Introducing The Hardline in 1987.

Image credit: Manuel Scrima

Epic Odyssey

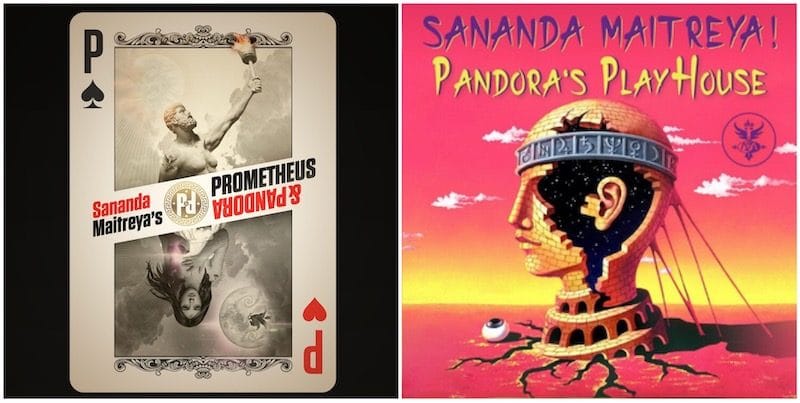

New album The Pegasus Project: Pegasus & The Swan completes a trilogy begun with 2017’s Prometheus & Pandora. Sananda admits of that first album about the story of Prometheus’ exile from Mount Olympus: “With Prometheus & Pandora, I might have been too precious about the lyrics. It was something I had to go through, so that with the next project, Pandora’s PlayHouse, I became more conscious to take some of the pressure off the words.”

Now, Sananda’s attitude to his lyrics is: “Not everything has to be me showing that I’m a son of the Romantic poets: I can just say some shit that fits. I blame Bob Dylan for fucking us all up. While it was hugely important for Dylan to demonstrate the capacity for depth and profundity in lyrics, even he will tell you he’s never written a more profound lyric than ‘A-wop-bop-a-loo-bop-a-wop-bam-boom.’ So, who’s smarter: Dylan or Little Richard?”

There’s a debate for the ages, and one that seems to sum up the dichotomy of Sananda Maitreya: half Dylan, half Little Richard. Ever since he left behind his original identity of Terence Trent D’Arby, the mainstream has treated Maitreya with suspicion. Because he won’t just sing Wishing Well and If You Let Me Stay on demand, he’s generally been seen as aloof and earnest. Not a bit of it. He’s enthusiastic about any subject put to him, and he’s a funny badass, too.

Asked about why his recent albums feature at least 30 songs each, Sananda responds: “Artists grow up undermined by so many clichés: nobody can write so many songs and have them be interesting, nobody writes interesting songs after a certain age. I love looking at those clichés and drawing a line through them one by one, while saying ‘Bullshit’.”

Rocking Horse

That said, Pegasus & The Swan wasn’t intended to be such an epic. It’s his 13th album. Thirteen is his favourite number, so Sananda had intended making a 13-song, guitar-focused album to mark the occasion. Then, around his 60th birthday in 2022, he realised it was instead time to try to complete the Prometheus cycle. The result is an adventurous and captivating 41-track epic, loosely divided into the more rocking Pegasus side, with The Swan’s songs incorporating theatrical ballads, operatic extravagance, and moments of tranquil respite. There’s also plenty of the hypnotic soul/pop hybrid that first made his name.

Maitreya is aware that, for casual listeners, his tracklisting looks a lot to contend with. “I can’t take credit for being prolific,” he shrugs. “I may as well belong to Apple, as I’m a phone. Everything coming through me is because I’m designed to do this. My prolific nature is hardwired into me.

“Besides my family life, there’s nothing else that really fulfils my divine dissatisfaction. I use my time efficiently, and having songs reveal themselves to me is exciting. But I’ve said to my wife that I’ve got to slow down. I don’t have to have 40-song projects. I’m a Capricorn Rising, a mountain goat, so it’s in my nature to climb. But that mountain is mine and I don’t have to climb to anyone’s phase but my own. So I can just do 13 songs.” A laugh. “But that’s how this one was supposed to start. Once the green light is on in the studio, it takes over you.”

London Calling

Typical of that compulsion to get things done was adding the unusually nostalgic Camden Town as the album’s 41st song, just when Sananda thought he was done. It’s a simple banger describing how Maitreya first moved to London from Germany in the mid-80s. He lived in his manager’s North London flat and the mischief in the song might not be entirely fictional.

“I’m not really one for nostalgia,” says Maitreya, with uncharacteristic understatement. “I’ve still too much work to do to be influenced by the weight of what I’ve done in my past. Nostalgia creates its own vortex. Once you start looking over your shoulder, you have those reflexes, so you’re always doing that. It’s not that time yet, so I didn’t think I needed this song.”

But the song was so insistent, it essentially demanded to be made. “It came to me intact, going: ‘I’m making it easy for you here,’” laughs Sananda. “It had to be taken seriously. I knew if I didn’t record it, it’d be buzzing around in my head, like a fly in the kitchen, for the next two years until my next project. I couldn’t take that.”

Camden Town has echoes of another of the area’s residents, Amy Winehouse. “I never met Amy, but I was told she was a fan of mine,” Maitreya explains. “She lived close in Camden to where I did. When I heard her record Frank, it struck me how much it bears Camden’s feel. To motivate myself, I sometimes write songs for other people. My aim with Camden Town was: ‘Amy would appreciate this.’”

Image credit: Manuel Scrima

Supreme Being

The UK was first to discover his talent, but it’s also where Sananda’s defenestration from the music industry occurred following 1989’s polarising second album Neither Fish Nor Flesh. It’s left Maitreya reluctant to play here: he hasn’t done so since 2002, when audiences were trying to get accustomed to Sananda Maitreya instead of Terence Trent D’Arby.

Finally, at Love Supreme festival in Sussex on 6 July, Sananda played here again. He enthuses: “England is emotionally important to me. England was the mother of my career. My last incarnation was birthed in England. Then, as soon as she gave birth to me, she mocked me and told me to fuck off. So, playing in England is impregnated with a great deal of controversy, excitement and some residual bitterness and heartbreak. It took me a longer time than I’d care to admit to get beyond that.”

Aware that many refuse to look beyond his releases under his former name, Sananda reasons: “Until the scene was ready to fully acknowledge the reality I’ve existed in since the mid-90s, there was no point in me coming to England. Having already been mocked once, I wouldn’t allow myself to be mocked twice. But, so long as I’m working on my terms, I’m comfortable going anywhere.”

Picture credit: Manuel Scrima

Introducing The Hardline

On the idea of singing his old material, Sananda explains: “I operate under the assumption that, whatever it is I do, I’m going to come onstage, grab your balls and take them for a squeeze! That’s what it’s about, not the idea that I have to be liked with everything I do.”

A well-honed live band, The Sugar Plum Pharaohs, is in place to back Maitreya when he tours this year. But, bar a string quartet and an orchestra helmed by leading conductor Diego Basso, Sananda plays everything on the new album himself. “My one proviso for doing it all myself is that I didn’t want the songs to sound like a one-man-band,” he emphasises.

“I sometimes hear albums where I can tell if someone has done it all themselves. If you don’t know it’s me doing it, I want you to think: ‘Hey, that’s a pretty cool band behind him.’”

That virtuosity has been present since childhood. He grins: “I can take a vacuum cleaner and get a song out of it. As a boy, one of the most exciting times was when my mother would vacuum the house, as I’d start harmonising with its drone. At the heart of it all, I’m an arranger.”

Musical Education

Sananda also feels fortunate to have grown up in Florida, surrounded by so many different types of music. “If you want a musical education, there’s no better place to be raised,” he reflects. “A gig was a gig, so if someone said they needed a bassist, you raised your hand. Same if someone needed a fiddle player. Later, people looked at me and said: ‘Oh my god, he plays all these instruments!’, but it just wasn’t a thing when I was a kid. It was just part of the culture I came through.”

Has any instrument defeated him? “There’s nothing I can’t play that I’m interested in playing. But as a boy, I saw a trumpeter open his valve to let the spit out. That was: ‘Eurgh, no thanks!’ If there’s spit involved, you’ve lost me, so I’ve never been drawn to horns.”

Being able to function so prolifically is one reason Maitreya has little time for his past. It’s not that he’s ungrateful to the music that made him, he’s simply more excited by what’s next. Sananda explains: “After I master a record, I generally don’t listen to it again. I’m already moving onto the next thing and don’t like dwelling on what I could have done differently.”

Self Made

Despite seeking to maintain that distance from his old songs, Maitreya was delighted when, by chance, he recently heard a song – he forgets which – from his 2011 album The Sphinx. Before realising it was his own song, he’d loved its intro and thought “I need to write a song like this.” There’s another laugh: “That’s the good side of being prolific. I do occasionally look at a song I wrote in my twenties and think: ‘How the fuck did you come up with that? You weren’t on drugs and you wrote that? How did I know that stuff?’ It’s not that the song has a universal truth to impart, more that it’ll pre-shadow what I’d go through later in my life – and it nails it.”

Sananda feels the same precocious wisdom from Tracy Chapman, whose self-titled debut album was released the year after Introducing The Hardline. He loved Tracy’s acclaimed recent Grammys performance of Fast Car and admits: “I slept on that song. At the time, I thought it was good, but I didn’t think it was great. But the timelessness of Fast Car, how universal it is? A hundred years from now, Fast Car will still be relevant and consequential.”

Bringing Sexy Back

While most people in Britain haven’t had a chance to see Sananda Maitreya for over 20 years, Classic Pop is happy to report he’s aged as well as you’d hope. Even with a navy beanie covering his hair, Sananda is distressingly handsome, casually bearded and eyes glinting with mischief as he discusses the sensual pop of new tunes Bondage and The Things U Like, laughing: “Sexy sells. I’m certainly trying to capture feeling sexy in those songs.”

Such Princely earthiness typifies an album Maitreya feels is “more primary coloured” than his previous LP, Pandora’s PlayHouse. “Before each album, I’ll assign a gender to it,” he notes. “Does it feel more divine feminine, divine masculine, Shiva the destroyer, Krishna the nurturer? It gives a sonic identity and helps me choose the instruments, down to which pick-ups on the guitars to deploy.

“Then you notice little footprints going somewhere in the songs. You’re on the kitchen floor, going: ‘Where do these little mouse prints lead? This is where it comes from, this is where it goes back out. Aha!’ The footsteps make you see a pattern to where you’ve been going.”

Planning both a documentary about his life and a musical based on telling his story through his Promethean album cycle, Maitreya won’t be slowing down any time soon. That shorter guitar-based album might just be his next project.

Whatever happens, Sananda Maitreya will be living his best life. On one condition. “At some point, I’ve got to play you some music,” he reasons. “Every now and again, the bear has to come out of the cave.”

For more information on Sananda Maitreya click here

Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.