Annie Lennox and Dave Stewart’s third album proved they were no flash in the pan. Eurythmics’ Touch was a rich and expansive collection of tracks, at various points majestic or downright funky, that helped to cement their place in pop history.

Early success can be the death of a burgeoning artist, suddenly thrust into the spotlight and then tasked with repeating the feat. No such worries for former flames, Annie Lennox and Dave Stewart. By the time they ascended to the summit of the Billboard Hot 100 at the start of 1983, the ‘hot new act’ were already industry old-timers. Sweet Dreams (Are Made of This) was actually their fifth studio album together, including the three long-players in two years by New Wave hopefuls, The Tourists – and that’s before we get on to Dave Stewart’s two long-forgotten, early-70s records with the folk group, Longdancer.

So, when the time came to follow up the Eurythmics’ breakthrough, it was not so much the ‘difficult second album’, but rather business as usual. Touch was the duo’s third studio LP under their new moniker – their second within the same year, in what amounts to an extremely prolific run of productivity. The progression is equally impressive. Where its lo-fi predecessor is grittier and more dystopian, Touch is comparatively lusher sonically, bolder in production, and (at times) much funkier and more playful.

Business As Usual

Unlike so many classic albums to grace these pages, Touch is not the tortured tale of protracted sessions, spent aching over each syllable. In fact, Touch was both recorded and mixed in just three weeks – a phenomenal work ethic that would put many of their contemporaries to shame.

Such a pace might be standard fare for a rough-and-ready garage band, essentially knocking out their live set on tape. But Touch is something else entirely: a precise, meticulously produced and multi-layered work; a shiny and ambitious pop effort, peppered with subtle flourishes that only reveal themselves over time.

Of course, the release was expedited to satiate the sudden huge demand for the duo who until recently had languished in relative obscurity. Certainly, the pair must have felt some pressure to deliver the goods. And fast. Speaking to The Tube in October 1983, Annie (ever the realist) acknowledged: “Well, we had a schedule to meet.”

Shiny And Ambitious

Meanwhile, in the same interview, Dave proffered a more optimistic take: “Well, I think it was better for us to make the album in such a fast way, because we’d come straight off the stage playing live, lots of concerts, and we captured that on the record. And I think a lot of people spend too long in the studio messing around, and this particular album has benefitted from it I think.”

Indeed, Touch sounds fantastic by any standards, neither thrown together nor overly tinkered with. In reality, the two had by now found their form, with inspiration pouring out to shore up their position.

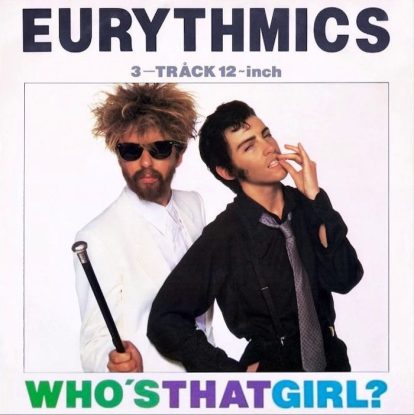

While the standard of production is exemplary, it nonetheless wears its flaws outwardly. Throughout, capturing the raw energy and emotion is always afforded greater importance than achieving technical perfection, as a wavering vocal on the opening verse of Who’s That Girl? demonstrates. It’s refreshing to today’s ears to hear a track that hasn’t had its character sucked out of it through the ubiquitous pitch correction tools.

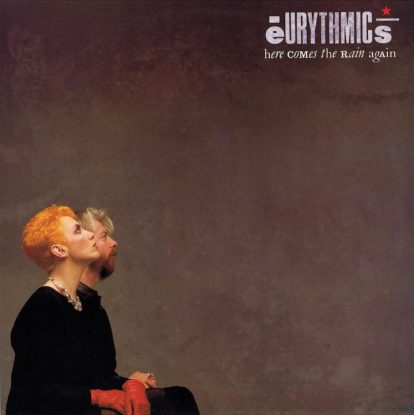

When it came to preparing for the album, Lennox and Stewart got a good head start, writing and demoing together on their drum machines and synths while on tour. Indeed, opener Here Comes The Rain Again was penned spontaneously on a rainy day, camped up in a New York hotel room overlooking Central Park.

Raw Energy

By mid-1983, the duo had developed a distinctive and winning sound. Meanwhile, the resultant success gave them the confidence to both consolidate that sound and deviate from it. The ultimate offshoot is an album that’s classic Eurythmics, though also eclectic and expansive.

The album was recorded in its entirety in the upstairs room of a former church in London’s Crouch End. Shortly before release, Dave explained the set-up to The Tube: “It’s really like a little warehouse, you know, so it’s not like a proper recording studio, and it works better for us like that.” He elaborated further on Swedish TV in the same year: “We wanted to get away from the industry, where it’s a factory line, where the next group goes in the studio, then the next group goes in after, and it’s just a sausage factory…”

At a time when the big studios still dominated the industry and home recording was unheard of, this was a bold move. This freedom created an environment in which they could work at their own pace, without the associated costs and inference andwith fantastic results. Under their tutelage, ‘The Church’ would grow from these humble beginnings to become an esteemed studio, later owned by David Gray and now producer Paul Epworth, welcoming everyone from Bob Dylan to Madonna.

Take Me To Church

Touch saw the pair expand their musical palette, opting for a greater balance of acoustic and stringed instruments. Amazingly, even the string section from the British Philharmonic Orchestra was captured in their relatively cosy studio space. Apparently, (to quote rockandrollglobe.com) this entailed “cello players… positioned in the bathroom with violinists in the hall and arranger Michael Kamen conducting from a spiral staircase.”

The calibre of guest musicians on the album is second to none. Sid Sax (who, in fact, played the violin) is called out “with special thanks” in the liner notes. A favourite of George Martin, pop trivia nuts won’t need reminding that Sax’s previous session credits included Beatles standards, Yesterday and Eleanor Rigby.

The resulting work is sophisticated, well-crafted and – at times – majestic, most notably on Here Comes The Rain Again and the fantastic No Fear, No Hate, No Pain (No Broken Hearts). Often, it dips a toe in the avant-garde, but throughout itremains fundamentally a pop album, and an extremely accessible one at that. Even at their more outlandish or dramatic moments, Annie and Dave manage to pull it off without ever sounding pompous or worthy.

Magic Moments

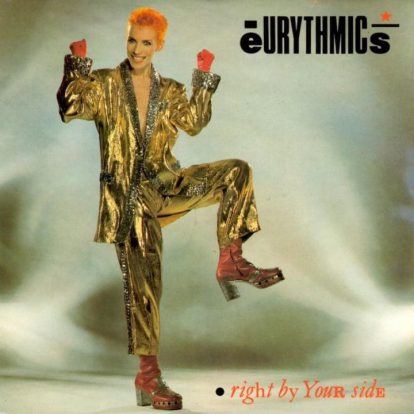

Across the album’s 45 minutes, Annie conveys opposing emotions – sometimes aloof and guarded, at other times, raw release. The jaded lyrical themes of their previous record continue: mistrust, jealousy, guarded rage, yet the warmer orchestration injects welcome rays of light among the darkness. In Right By Your Side, however, it’s just pure light, beamed straight in from the Caribbean on a wave of steel pans.

With the synth honeymoon perhaps beginning to wear off, Stewart is content to dust off his old guitar again, and he wields it with intent in the live performances of this era. Nevertheless, he plays his guitar hero ambitions very lightly on Touch.

Of course, a more muscular guitar sound (with long hair to match) would follow in the late 80s. But for now, Dave’s happy to simply let his subtle embellishments serve the song, whether that’s slinky Chic-esque licks or dub-style flourishes.

Who’s That Girl?

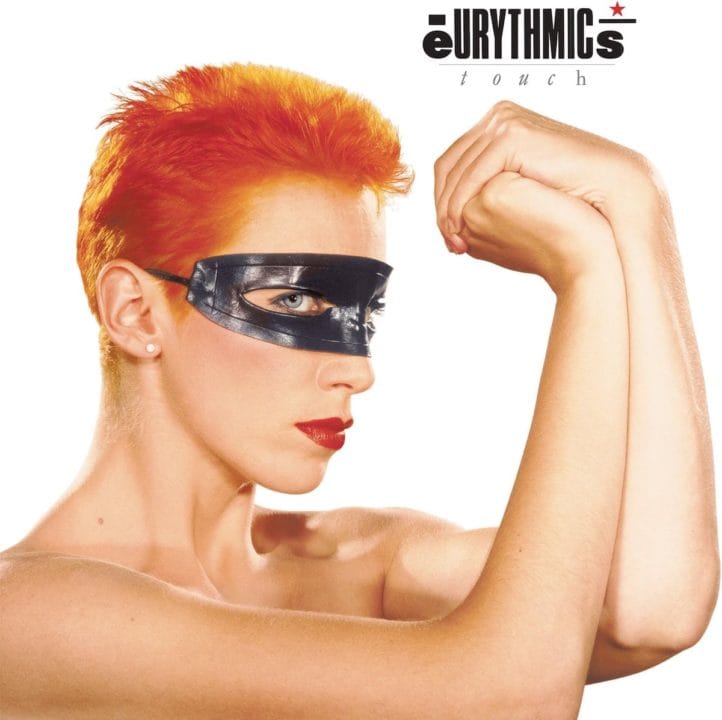

The album possessed that ultimate hallmark of quality, prized by every self-respecting artist of the 80s: a Peter Ashworth cover photo. The photographer is renowned for immortalising icons in that wonderful 12” square format (as he did for other luminaries of the era: Adam And The Ants, Visage and Frankie Goes To Hollywood.

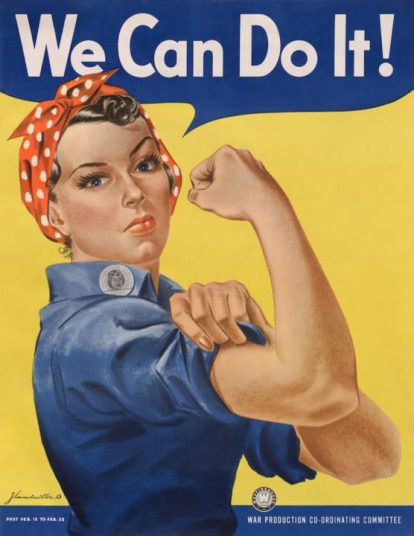

But Touch is one of Ashworth’s finest: Annie adorns her classic tangerine buzzcut and leather Lone Ranger mask, like the ultimate superhero she is, flexing her muscles in a pose reminiscent of J. Howard Miller’s 1943 promotional poster, ‘We Can Do It!’

That original poster was designed to inspire the largely female factory workforce (so-called ‘Rosie the Riveter’) during World War II. The similarity is not incidental – the image was often re-appropriated as a symbol of feminism in the 1980s. The cultural importance of Annie’s own iteration is assured by its inclusion in the National Portrait Gallery’s permanent collection.

Credit: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration

Musical Milestone

While Lennox is forever the icon, Touch represents a significant personal achievement for Dave Stewart, too, being his first record credited as the sole producer. This milestone would prove instrumental in launching his parallel career as producer for the heavyweight stars, which has included a Beatle, a Stone and a Heartbreaker.

Like Yazoo and Pet Shop Boys, Eurythmics had helped to create the British synth-pop duo archetype – strong silent type at the back, twiddling the knobs; theatrical frontperson commanding the audience.

While they actively nurtured that aesthetic on the Sweet Dreams album, Touch marks a conscious move away from it, evident in the newly expanded live band (complete with a trio of matching backing singers dubbed ‘The Croquettes’), who are pointedly showcased throughout promotional appearances.

A Touch Of Class

The only discernible fly in the ointment in its immediate aftermath was the release of 1984’s Touch Dance – a hotch-potch of dance remixes, hastily assembled and released without the duo’s input, and much to their chagrin. There was no disguising the cynical label cash-in on this occasion.

Yet with Touch recently celebrating its 40th birthday, it remains totally fresh and relevant as it ever was. As a collective body of work, it’s a record that cements Eurythmics’ place in pop history. It was their first, but not last, No.1 album. While it essentially retained and perfected the synth-pop sound, it precipitated further sonic departures on subsequent LPs.

Touch made it onto Rolling Stone magazine’s ‘500 Greatest Albums of All Time’ list in 2003, and again in 2012, among other vaunted picks of essential listening, and rightly so. Though not without flaws, it’s a touch of class.

The Songs

Here Comes The Rain Again

A lyrical counterpoint to George Harrison’s sunny optimism perhaps. The album opens much where things left off, with a minimalist arpeggiating synth invoking the club – but the orchestral arrangements from Michael Kamen add organic, human warmth. It possesses all the characteristics we’ve come to know and expect from a Eurythmics record: deep, soulful vocals from Annie Lennox, laced with yearning, plus shimmering electronic production from Dave Stewart, building into a killer chorus. Stewart has explained how part of the song’s tension is derived from its key hovering between a minor then its parallel major, leaving an unresolved and undecided feeling. It reached No.8 in the UK, and No.4 in the US.

Regrets

While the Eurythmics are one of those groups with their own clearly defined identity, Regrets has more than an echo of Grace Jones in her early 80s Compass Point period. With its minimalist slinky swagger, and skittish rhythms, it really could be a tribute to the Jamaican star, who was in her element in this period. In fact, the comparison has often been made between Jones and Lennox, both style icons of the 80s with a bold angular and androgynous aesthetic. An innovative slice of pop and early highlight of the record.

Right By Your Side

Again, that Compass Point flavour carries through, though in a more upbeat melodic sense. Right By Your Side has an overtly Caribbean vibe, with shuffling calypso grooves, skittish drum machines, slinky guitars from Dave Stewart, and even synthesized steel pans thrown in just to seal the deal. In fact, it’s really setting the template for Vampire Weekend. Even down to the upbeat lyrics, it really couldn’t be any further from the cold, mechanical desolation of Sweet Dreams released earlier that year. Annie even breaks into scat with pure jubilation.

To a greater extent, it’s an obvious outlier in its joyous, unbridled optimism, compared to the more restrained and cool nature largely adopted elsewhere. Indeed, this is the track that most polarises fans and critics, with several observers finding it just a little too jolly for its own good. But perhaps that was the whole point: a firm statement from the pair not to be pigeonholed as producers of cold mechanical laments. Some observers have suggested similarities in the opening drum groove to Tom Petty’s Don’t Come Around Here No More, co-written and produced by Stewart soon after.

Cool Blue

More of a club banger, with a four-to-the-floor drum beat, repetitive groove and frantic beats. Cool Blue exhibits relatively minimal instrumental with a rather funky, rubbery fretless bass, popping, sliding and slapping over the place, subtly enhanced with cool, dub-style tape echo guitar stabs. There’s a range of contemporary US influences on display, including more than a hint of the Minneapolis sound on the chorus, with perhaps a little bit of Chic thrown in there for good measure.

Then, there’s even a nod to rap in Annie’s “How did you fall for a boy like that?” chanted refrain, that’s playfully pitch-shifted out of shape. Annie moves from the simple drawn-out legato lines of the verse, into the huge and energetic chorus on the “How can I forget you, baby? Never gonna give you up.” Dean Garcia delivers an extended bass outro, with a call-and-response going on with the synth pads, before Annie’s return for the chorus coda.

Who’s That Girl?

Sung from the perspective of a jilted lover, it’s a classic slow-builder, gathering momentum from subdued beginnings. It would become one of the duo’s most recognised hits in their native UK (rising to No.3), while fairing slightly less well Stateside, just falling short of the Top 20. For this writer, this track will forever recall a brief sketch from Harry Enfield and Paul Whitehouse as market stall fish sellers trying to remember the words and melody to the main hook. (If that doesn’t ring any bells, then Google it. But be warned, you’ll never hear the song in the same light again.)

The First Cut

Picking up where Cool Blue left off, it’s a repetitive club belter. Kick-starting on a slinky trebly guitar seemingly plugged straight into the mixing desk, plus a nagging synth riff that’s extremely reminiscent of something else – somewhere between early Depeche Mode and The Cure’s The Walk. It’s an example of the pair let loose in their church studio, having fun with the overdubs. Cue lots of staccato chants, synth pops and electronic whooshes that punctuate the track. Again, Garcia’s funky slap bass is a defining feature. It plays into Stewart’s notion of benefitting from months on the stage – despite the electro flourishes, it has a live jamming quality to it, with lots of guitar to the fore, compared to some more reserved tracks.

Aqua

A repetitive skulking groove, like the soundtrack to an alley cat on the prowl at midnight. Here, a spacious arrangement leaves room for Annie’s powerhouse soul vocal, heightened by cool counterpoint backing that appears to take influence from African traditional choral music. Staccato BVs, and great panning swooshing effects from Dave add further spice to the mix. Halfway through, the track adopts a palpable hypnotic quality, now taking on an Indian influence with a vaguely sitar-esque droning sound, before returning to a more syncopated funky groove. What it all means is unclear, with oblique and opaque lyrics. But what may sound like a stylistic mess on paper works wonderfully on the ear.

No Fear, No Hate, No Pain (No Broken Hearts)

A stripped-back, minimalist track opening with an echoing drum machine loop and arpeggiated bassline, followed by a trademark soulful Annie wordless melodic intro (see notable examples on her solo debut, Diva, a decade later). It’s a slow-builder with a dystopian synth-wave feel: very angular and arty, with lots of space between staccato synth hits, and dramatic live strings arranged by Kamen, that stab and lunge like Norman Bates in the shower. It’s the perfect vehicle for Annie both as singer and theatrical performer. A Pop Goes the Year appearance from 1983 sees Annie rooted to the spot, delivering a huge performance, her facial expressions and hand gesticulations alone conveying the power and emotion of the track. A huge artistic endeavour that represents Eurythmics at their very best. Evidently too subtle and skulking to enjoy a single release, but it remains a stand-out album cut and fan favourite.

Paint A Rumour

Now it’s back to electro club banger mode, with a thumping programmed kick drum and 8-bit computer game synths. By design it’s a repetitive backing track built on revolving grooves. As it develops, occasional brass licks enter the fray to present a more organic feel, before the release when it switches mood from the mechanical to a very organic slinky fretless slap bass, courtesy of Garcia.

With its experimental groove, looping tension, and absence of a discernible chorus (simply Annie almost chanting over the groove), it feels very much like an album track – and seven minutes long at that. It’s a chance to have a bit of fun in the studio and indulge their avant-garde side, though this writer will argue that no pop song has the right to outstay its welcome for seven whole minutes – not even Bohemian Rhapsody dares to do that. Still, it keeps one foot clearly in the club.

For more on Eurythmics click here

Read more: Album By Album: Eurythmics

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.