Picture credit: Naomi Davison

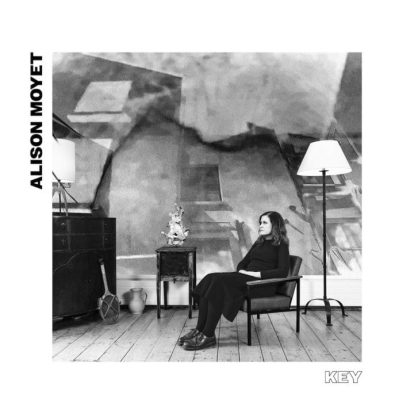

To mark Alison Moyet’s 40th anniversary as a solo artist, she’s revisiting old songs for her new album, Key. The record is also an excuse to tour – and to reflect on the constant turmoil that’s happened since Alf. Now Alison reveals all to Classic Pop about the trauma of fame, going incognito as an art student and the “physical euphoria” of keeping it real as a singer.

When most artists disappear for seven years between albums, the cause is generally writer’s block or an extended holiday. Alison Moyet is different. Since her previous record Other in 2017, Moyet has gained a First in a Fine Art Printmaking degree from her local Brighton University.

This shouldn’t be wholly unexpected: when she spoke to Classic Pop around Other, Alison was passionate about sculpting, completing a college course after her previous studio album The Minutes. Initially conceiving her degree as something to do during lockdown, she also had a more long-lasting desire for formal learning.

“I left school at 16 and had a chip on my shoulder about not having an education,” says Moyet, at the quiet upstairs bar of a discreet hotel just off Brighton’s seafront. “I thought music would be a job I’d do for a year. Had I done anything else, it would have been art: not because I have any great talent for it, but because it’s where my mind calms.”

Happy House

Alison has ADHD. For her, the condition partly manifests itself in hyperfocus. Once she is interested in something, be it songwriting or DIY, it takes her whole attention. Art is a rare escape where Moyet can still let the outside world in. As she puts it: “I can hyperfocus, without noticing the light hasn’t gone on until I’m sitting in darkness. Art is a clear place for me, a happy place.”

Her father Michel had also been a lithographic printer. “I grew up around the smell of ink,” she recalls. “We lived in a council house in Basildon, but one which had impressive lithographs around the place. Print was ingrained in my psyche.” However, when she told her father she might be interested in following his career, he sternly warned her it was a closed shop. Women weren’t welcome.

Printmaking was therefore a natural subject to eventually study, but Alison says of her degree, which she received in July 2023: “I don’t know if ‘enjoy’ is the word for it. I find it hard not to hyperfocus, so I worked really long hours. I’d be at school for 8.30am, stay until 8pm, then work all weekend. I was absent from my family and didn’t see anybody. I was so driven, but I was also enthralled. Being around young people reminded about art for art’s sake.”

A New Identity

Enrolling under her real first name of Geneviève and her married name, Ballard, Moyet was incognito for the first two years. “In the foundation year, during one lunchbreak two girls started dancing round the room singing Don’t Go,” she smiles, delighted that Yazoo’s classic still resonates. “Normally, if I can pretend I’m someone else, I do. But seeing that girl sing Don’t Go, I thought: ‘Shall I tell her, shan’t I?’ In the end, I told her: ‘That’s my song.’ She carried on dancing and said: ‘Is it? My mum’s is Love Shack.’” Alison delivers the pay-off with such perfect timing that your writer is still laughing while typing this feature.

Moyet was “charmed, delighted” to still not be recognised by her dancing coursemate, saying of when news in her third year broke that there was An Actual Popstar in their midst: “I was side-eyed for a day, it was a bit ‘Blimey!’ Not because it was me, but because the students couldn’t imagine anyone who’s lived that life being in their environment.

“For the degree, I had to do a Professional Development file, which included putting in my CV. My CV looked so wanky. One question is: ‘What will you do next?’ ‘Go back to my day job as a singer.’”

Turning Point

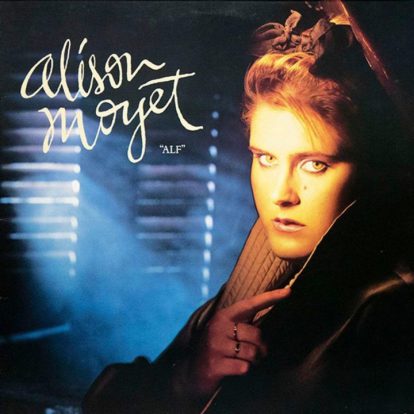

Indeed, Alison is with Classic Pop by the seaside because she’s back to the day job. It’s 40 years since Love Resurrection became her first solo hit, with her extremely-platinum debut album Alf arriving in November 1984. New album Key reworks 16 old Moyet tracks, adding two elegant new tunes co-penned with her regular songwriting partner Sean McGhee, who produces Alison for the first time, too.

“I’ve wanted to redress quite a few songs for a long time,” admits Moyet of the impetus behind the re-recordings. “The 40th anniversary means there’s a reason to do so. There were times when I’ve made records when certain sounds were de rigeur and haven’t aged well, which became very irritating.”

She cites 2007’s The Turn as particularly troublesome. “That album has some good songs that just weren’t realised,” she frets. “It came when there was little interest in me. That’s understandable, as people can’t stay focused on one act forever. It means some songs felt like unborn children, whose pregnancy goes on forever. I’ve tried to give birth to these songs in such a way they don’t just end up with a face only a mother can love.”

A Life In Turmoil

Admitting she was up against time constraints to even create two new songs – “I was on holiday in a field with my laptop” – it’s important to Alison that Key doesn’t imply her story is finished. Instead, Key is intended as: “A way to understand where I’ve ended up, and to show people can visit my other albums as if they’re rooms.” Moyet’s explanation of how she views her catalogue is typically fabulous: “Some rooms are double-aspect and beautifully laid out. Others are my room of shame, where all the shit gets thrown when people come round. That’s bound to happen during a life in turmoil like mine. It’s not a negative thing, but my life is always in turmoil, tumbling from one thing to the next.”

Alison didn’t feel the need to readdress her two most recent albums, The Minutes and Other. She’s similarly satisfied with 2002’s Hometime, made with Bristolian production team The Insects. “They’re aesthetically the place I want to be,” says Moyet.

The commercial years, however? Well. “I always had the hardest time with the hits,” she admits. “That’s more to do with how they completely defined me, as opposed to a criticism of the songs.”

The Fame Game

You may have gathered by now that Alison Moyet is brilliant company: funny, fully engaging with questions, blessed with a proper perspective on what she has achieved since Yazoo. She deservedly has a top-tier reputation amongst journalists for being equally kind and entertaining. She’s still highly punk, yer Moyet. But the 1984 Alison who had been left bamboozled by Vince Clarke’s decision to terminate Yazoo struggled with the huge success she achieved soon after.

“I was traumatised by fame,” she states simply. “I became agoraphobic and I was self-conscious.” Largely, this was because Moyet felt on her own as a solo musician. Another reason she values Sean McGhee so much is in having a proper bandmate, with the singer/keyboardist joining the ex-Scissor Sisters musician John Garden in Alison’s live band. It’s a contrast to earlier tours, where she was around session musicians who were gifted, but who had no kinship with their notional leader.

“My first tours were terrifying,” she says. “I had gone straight into doing those shows with no concert vocabulary. When I struggled onstage, I had no idea how to tell anyone to fix it. There was no connection with the other musicians, so I felt on my own.

“With session musicians, if you lose, you lose alone. When it goes tits up, everyone else can go on to the next job. That’s understandable, because when the big benefits happen, I get them. But if you face a hostile crowd, there’s no one to have a sly look with, whereas if it’s brilliant, there’s no one to share that joy with. Having Sean there, there’s trust that someone knows your language.”

All Cried Out

As “brilliant” as Yazoo was, Alison hadn’t felt a personal connection with Clarke either. After their split, “Nobody was there to adjust me to what it meant.” Instant solo success and its resulting fame left Alison so panicked that a popular misconception has evolved that she hates Alf, the album that caused her stardom.

“Alf has lots to commend it,” emphasises Moyet. “I was hot property when I made it, but that was from Yazoo, and Yazoo had been a creative experience. So was Alf. I was still untainted and uncynical. I wasn’t looking out for the pitfalls, so there is a lot of joy to that album.” She credits producers Jolley & Swain for “having interest in me as an artist” in helping Alf be “easy and uncomplicated,” recalling writing All Cried Out in just an hour in her Basildon kitchen.

Of that period, Alison reflects: “Alf has been a good friend to me. Any negativity I had towards it was from the fame I associated with the record. It’s like when you’re in love with someone and they dump you. It isn’t until later that you realise: ‘No, they were lovely, it was just circumstances that were wrong.’ The level of success from Alf prohibited me making the same creative moves I’d had going from Yazoo to Alf, because everyone expected more of the same.”

Primal Escape

There are two big hit songs which Moyet no longer sings live, Invisible and Weak In The Presence Of Beauty. The latter opens second album Raindancing, another very-platinum LP. Originally by Sheffield jazz-funkers Floy Joy, Alison sensed Weak In The Presence Of Beauty would be a hit if she covered it. In 1987, Alison Moyet was commercially bulletproof. Her version reached UK No.6.

Having admitted her cover was cynically recorded just to keep the chart action coming, could Alison have continued making hits to order? “I could,” she nods. She looks briefly pained at the idea of what could have been, before smiling, knowing that, by 2024, Moyet ultimately coped okay. “Without sounding a massive wanker, when it works as a singer is when you bring your true self to the work. I don’t enjoy ticking boxes.”

There follows an explanation of the importance of singing to Alison: “When I’m singing and it feels good, there’s a physical euphoria. The way I connect with oxygen, the way I open my mouth to a certain shape: there’s a primal escape in singing. It’s glorious, and I don’t make a good pretender. If I’m onstage counting down the songs – ‘Only four more to go!’ – that’s the worst deception possible for an audience.”

Pragmatic Approach

Written by Lamont Dozier of Holland-Dozier-Holland, Invisible troubles Moyet because of its Americanised language and because: “It’s a song about someone who needs someone else to affirm them. That’s not who I am. If someone is being that much of an arsehole to me, I’d kick them into touch. I won’t whine about them, I’m much more pragmatic than that.”

Alison is quick to point out she doesn’t dismiss anyone else’s love of those hits – “We all engage with music in different ways and songs can become important for people at different times” – but she admits that revisiting Invisible and Weak… for Key wasn’t happening: “I tried to say to myself: ‘Come on, re-listen to them, maybe you’ll find something to engage with again,’ but I just can’t do it.”

If the success of her first two albums left Alison feeling creatively stifled at being marched down a certain path, by 1994’s fourth LP Essex, her label Sony were fed up at having a popstar on the books who wasn’t playing ball. “I was yesterday’s act, not only selling less well but not doing what they think I should be doing to rectify that,” is Moyet’s pithy summary of the label’s attitude a decade after Alf.

Still Seething…

Alison’s tale of rejecting crappy material offered by her lackadaisical A&R rep around Essex is a black farce. “Those songs never turned up in anyone else’s repertoire,” she notes. Her usual good humour vanishes, as Moyet is still righteously seething at Sony’s treatment of her in the mid-90s: “I told the A&R: ‘I know you see no merit in these songs. You’re just ticking a box that says: “I’ve taken some songs to Alison Moyet.”’ Everyone else had already turned those songs down, knowing they were godawful. Sony didn’t trust my choice, but they didn’t care enough to think about their own choice either.”

Despite the battles, Alison created a “rough, scratchy” fascinating studio album in Essex, which she and her subsequent new A&R rep loved. Sony did not love it, making Alison re-record the album with Ian Broudie. “Ian did a great job on those songs,” sighs Moyet.

“But the songs had had their moment. Sony stepped back, as they were just pissed off with me by then.” That new A&R who had championed the initial Essex was Rob Stringer: now the worldwide head of Sony.

Shakespearean Misunderstanding

Key features a new version of My Best Day, initially recorded with Broudie for Essex, but which ultimately instead featured on The Lightning Seeds’ 1994 LP Jollification. “I should have released My Best Day as my own single, and it’s my fault that I didn’t,” tuts Alison. From its demo, Ian told her Sony thought it was sounding like a single. Moyet grimaces as she admits: “I thought Ian meant: ‘The label want it as a single. Sorry, I’m sure you can guess why.’ He didn’t mean it that way at all, but I only found that out later. Ian was up for the idea, and I would’ve been, too.”

Instead, My Best Day became “a Shakespearean misunderstanding” of singer and producer assuming each other hated what they both thought in reality was a great pop nugget. “It’s one of my best bits of sardonic writing,” she reflects. “Alongside So Am I from Essex, there’s a humorous tone marrying those songs together.”

Woman In Chains

If losing a great single was bad enough, Alison’s luck was about to get a lot worse. After Essex, it would be another eight years before Hometime finally became her fifth album in 2002, as Sony effectively dropped Moyet – while refusing to let her join another label.

“I don’t resent Sony losing interest, because I’d had a lot more interest in me than most singers ever get in their life,” she insists. “Wanting to drop me, that’s the natural way of things and none of that upset me. But they just wouldn’t release me. They wouldn’t take my calls and they wouldn’t let me work either. That was just cruel.”

Released on the now-defunct Sanctuary Records, Hometime allowed Alison to remember why she wanted to make music. “If record label people didn’t care when I listen to them, why would I care if I don’t listen to them?” she ponders. “If I do what I want, I’ll either sell more records or I won’t.”

The Old Lady Of Wisdom

Moyet’s attitude to the industry’s treatment of her is summed up in The Impervious Me, one of the two new songs on Key alongside its first single, Such Small Ale. She says of the former: “That song is the lesson I had to learn, about how you can spend your life shapeshifting to try to match the room, trying to fit in. You always feel someone else is getting it right while you’re missing it.

“Invariably, you wake up one day and realise that the things you’re missing are the things you’re not impressed by anyway. You can’t engage because you’re not interested. That’s the place you need to arrive at, in order to become the impervious me.” She laughs, gazing around the near-deserted bar in mock fear at being overheard. “I’ve become the old lady of wisdom, always offering my wisdoms to people.”

More seriously, Moyet had to wise up quick once Alf sent her stratospheric. The industry, the media and the public didn’t know what to make of a commercially viable singer who was also still absolutely herself. “A lot of brutality is dealt out to gender-non-conforming, fat popstars,” she notes. “To a young woman, the insults are shocking and hateful. But in some ways, it was the greatest gift, because you become inured to it all.

“I had the most dehumanising, unflattering things said about me, both in headlines and getting it shouted at me, at partners and friends. It got to the point where I recognised some of those insults: ‘Yeah, I am that.’ Very few insults land with me now.”

Songs In The Key Of Life

While The Turn showed there were still bumps to come after Hometime, Alison has been able to follow her creativity unopposed since The Minutes in 2013. It’s been so smooth that her husband David thinks it’s unfair she can still sing with such power. She laughs: “When I played The Impervious Me to my husband, he told me: ‘You have no right to sound like that.’ I know what he means, because I never sing between tours. Three years can pass without me singing, beyond nursery rhymes to my grandchildren.”

She quickly demurs when asked if her voice could therefore be considered a gift. “The word ‘gift’ feels so aggrandising,” she counters. “My voice is an oddity of my make-up. My husband does yoga, long-distance cycling and running. His mindset to push his body is his gift. Some people have a body built to be an athlete or a dancer, my body is built for making sound.”

In marking her 40th anniversary as a solo turn, Moyet’s biggest desire, more than releasing Key, was to ensure she could tour. That will happen early next year. “I’m aware time is running short,” she considers of her voice’s strength. “Until I go to rehearsals, I’ll have no idea if I can still sing. I need to warm up, but otherwise I do no work. But I have a body that resonates for making sound. It hasn’t changed, other than I have to bring the keys down in some songs, because I now have a low voice and speak in a general whale tone.” (This, readers, is nonsense. Alison’s speaking voice is the distinctive but light Essex tone it always was.)

Finding A Voice

Moyet also attributes her voice’s good fortune to her upbringing in Basildon. “Asking who I’m trying to emulate has always been a strange question to me,” she muses. “I’ve never tried to emulate anyone, I always make the noise my body wants it to make. We had one record player in our house. Being the youngest, I was last to choose what to play. My brother listened to Family and The Who, my sister to Rod Stewart and soul. I was more influenced by Roger Daltrey than Barbra Streisand, or anyone the record company imagined I listened to.

“Streisand just isn’t where my voice comes from. Really, it comes from being in a family who had no inhibition about being dramatic. It was a lot of screaming and shouting, imposing yourself on somebody else through volume. It was anger and passion, maybe with Jacques Brel in the background. My voice was from not being self-conscious about being wrought, rather than about perfect singing.”

Pressed For Time

A year after graduating from Brighton University, Alison has designed the sleeve for Key, a dramatic self-portrait print. She’d previously done the stamp design for Essex’s artwork, but explains: “I was creative without the knowhow before now.” Moyet has a small print press at home and intends carrying on lithography. There’s also a full new album to consider.

“My biggest problem is my eternal list of things to do,” she says. “I flit between them all the time. My hardest task is to remember what all my tasks are.” With that, Alison Moyet finishes her still water. She’s off to collect some wood for a DIY job. It seems like Album 11 might have to wait a bit.

To buy Alison Moyet – Key click here

Check out our Alison Moyet – Key review

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.