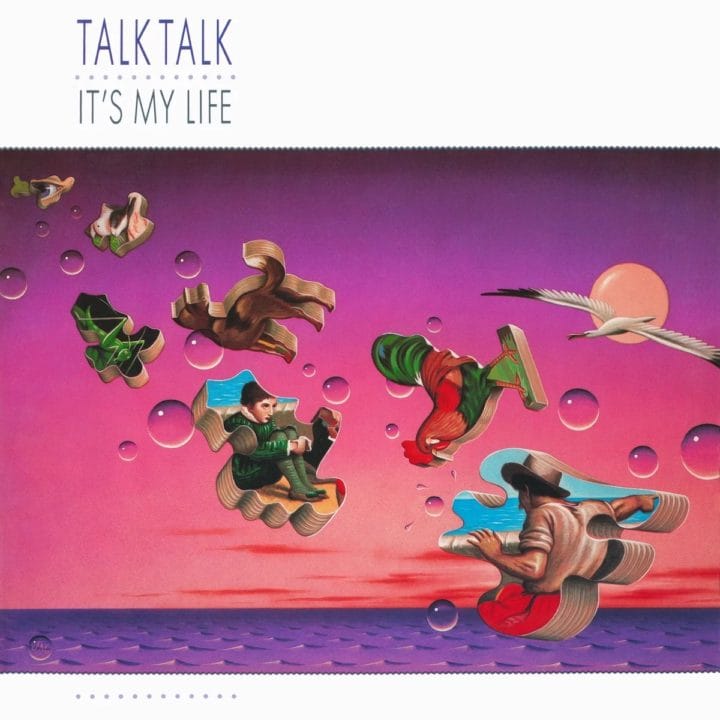

Initially ignored in the UK, Talk Talk’s second album, It’s My Life, marked the first signs of a shifting trajectory. But it stands up on its own merits as a fine synth-pop record.

Throughout life, there’s often a disconnect between the perception and the reality: where you are, versus where you want to be. This uneasy tension framed the career trajectory of Talk Talk in their formative years. Long before the critical plaudits and mythologising, they were largely dismissed as apologetic synth-pop also-rans. For all the talk talk, could they walk walk? From their early output alone, frontman Mark Hollis’ frequent allusions to John Coltrane and Debussy don’t immediately ring true.

What Hollis really stood for remains a fascination today, one that’s accentuated by his later self-imposed exile from the limelight. 40 years on from 1984’s international breakthrough, It’s My Life, and some five years after his passing, the mystique surrounding him only grows more impenetrable in the void he left behind. But while it’s the later post-rock masterpieces that prompt uncontrollable gushing from A-list fans (Robert Plant to Bon Iver), there’s plenty to savour in It’s My Life.

Arty Intentions

Like so many of their contemporaries, Talk Talk were initially presented as the next Duran Duran, before turning out to be a different beast entirely. Judging by their 1982 debut, The Party’s Over, it’s not hard to see how the comparisons arose. Riding the wake of the Fab Five’s second coming, it stemmed from the same record company, and the very same producer, Colin Thurston (in the words of Duran’s John Taylor, “a major catalyst for the 80s sound”). Cue soaring choruses laced with melodrama, bright synths and driving rock drums. Oh – and crisp white suits.

The likeness was not incidental, but carefully choreographed by EMI’s A&R machine, even if the young group might claim not to have got the memo. “I get depressed about the whole thing,” Hollis told Noise!. He may have had other plans, but the only element marking out Talk Talk’s arty intentions at this point (besides the snarky, anti-glam title) was the kooky sleeve by James Marsh. The antithesis of the Duran debut’s smouldering fashion shoot cover art,it opted for a whimsical painting owing more to surrealists Max Ernst and Salvador Dali.

Rise Of The Machines

Talk Talk’s second LP, It’s My Life, marks the first palpable shift in their musical trajectory. While ultimately a conventional pop record, again prepared under the watchful eye of the label, it nonetheless represents a conscious expansion of their sound. But it’s a subtle progression rather than radical departure, brought about through the introduction of more acoustic instruments, sophisticated chord sequences, and arrangements allowing greater space for each part to breathe.

Keen to distance himself from the ubiquitous electro-pop, Hollis saw synths as a necessary evil, begrudgingly tolerating their presence as a proxy for the orchestral instruments he couldn’t yet afford. “I hate the instrument”, he protested (perhaps too much) to Oor magazine, “especially when it turns into that ‘squeaky bonk plinky fumble’.” Flippant or not, the claim appears particularly disingenuous when this album is laced with them. Therein lies the issue: certainly at this point, the rhetoric doesn’t match the reality.

Nevertheless, with their original synth player Simon Brenner jettisoned after touring the first record, this heralded a move away from the traditional four-piece set-up, towards a selective use of instrumentation, as befit each track. As Hollis biographer, Ben Wardle, puts it in A Perfect Silence, “Now that the band was whittled down to a core trio, Hollis could bring in musicians to add colour without having to deal with the politics of finding them something to do in every song.”

All That Jazz

It’s the beginnings of Hollis the auteur, assuming greater control over Talk Talk’s aesthetic, attempting to close the gulf between the vision and the status quo. But in 1983, for all his professed love of Bartók and Miles Davis, he lacked the musical language to fully bring that vision into fruition.

A new catalyst was Jamaican British pianist, Phil Ramocon, who shared Hollis’ love of jazz, and opened up his approach to songwriting with exciting chord transitions and novel key changes.

Interviewed in Wardle’s A Perfect Silence, Ramocon highlights Hollis’ natural talent for effortlessly shifting from one key to another mid-song – a feat that would befuddle many a competent musician. This ability to modulate in an instant, added a distinct characteristic to their material, injecting subtle melodrama and dexterity into an otherwise standard pop song.

But it was new producer Tim Friese-Greene whose presence would prove most fortuitous. Hollis was initially attracted by Friese-Greene’s knack for getting inside a song without imposing his own aesthetic on it. Before long, Friese-Greene became Hollis’ primary co-writer. Like George Martin to The Beatles or Nigel Godrich to Radiohead, Friese-Greene would gradually evolve into an unofficial extra member, both deploying the studio as an instrument and facilitating access to orchestration previously beyond their reach.

Moody Detachment

Mark and Tim developed a workflow of extended experimentation with sounds and arrangements, searching for that little spark of magic. For Ian Curnow, another keyboard player brought into the melee, this meant “going round the houses” and embracing the mistakes. Speaking to Ben Wardle, Curnow remarked: “There’s a magic about a mistake because it’s not conscious – it’s like freeform jazz… Mark had a nose for that.’”

Hollis was keen to bring in the natural world, though ironically, the seagull and elephant sounds on the record were created on those dastardly synths, when field recordings at London Zoo failed to come up with the goods.

In its slower moments, the album is reminiscent of Depeche Mode, both in its moody detachment and use of stark looped percussion. Vocally, too, Hollis sounds uncannily like Martin Gore at times, with both sharing those long, legato phrases wrapped up with a quick vibrato at the end of the phrase. In time, Hollis would come to regard the voice as another texture in the wider composition, rather than a lead instrument or conduit for lyrics. And this may go some way towards explaining something that so often befuddled hapless critics, wondering what he stood for.

For all the fascination with Mark Hollis, it’s easy to sideline the other core members. Paul Webb’s rubbery fretless bass is an underappreciated but critical element of Talk Talk’s sound. His propulsive yet fluid parts (always prominent in the mix) are nothing short of sublime; a perfect counterpart to Hollis’ extended phrases, pushing each track onwards with forward momentum alongside Lee Harris’ athletic drums.

Call Of The Wild

For much of its genesis, the album went under the working title: ‘A Chameleon Hour’, only changed following the ubiquity of another recent Chameleon-themed hit (well, that’s karma for you). Clearly Hollis was still enamoured with the idea, though, as it would resurface on the next record’s Chameleon Day.

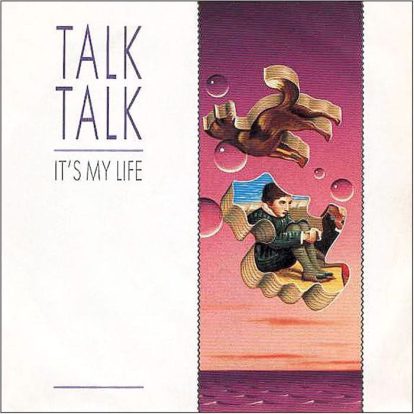

Again, James Marsh was called upon for the sleeve artwork, cementing a relationship that would endure for their entire career – typically drawing inspiration from nature, particularly bird and butterfly motifs. Here, he takes elements from the Victorian painting The Boyhood Of Raleigh, reimagined through Dali’s surrealism.

For a group so universally lauded, it’s almost inconceivable to imagine a time when Talk Talk were routinely trampled down to the point of persecution. The UK press were savage. If Hollis had hoped It’s My Life might silence the naysayers, he would have been disappointed. His latest artistic statement was described as “ugly” (Melody Maker), “limp and whiney” by the NME, and worst of all as “crushingly, excruciatingly average” by Record Mirror.

Such A Shame

Curiously, It’s My Life was released exactly one week before The Smiths’ eponymous debut LP in February 1984. While the two groups were clearly on very different trajectories, it’s impossible not to draw parallels in their shared disdain for synths and clichéd macho rockstar tropes. Yet the difference in perceived credibility at the time is palpable. The Smiths held the advantage of coming fresh out of the blocks fully realised, without preconception, and little disparity between the rhetoric and execution.

But while It’s My Life was all but ignored in the UK, it was another story in Europe and the US. Away from the domestic taunts, their sound was resonating internationally, and small ripples would make waves. Case in point: in the UK, Thompson Twins’ latest album rose to No.1, while It’s My Life limped in at No.35.

In the States, however, Talk Talk would knock them off the top spot of the Dance Chart. Meanwhile, Talk Talk’s popularity in Europe meant additional security to hold back the baying mobs – a very different scenario to that of the local pub back home.

Post-Rock Visionaries

Eventually, the UK cottoned on to what the rest of the word had long recognised. And so Talk Talk and Hollis have risen from “Duran without the lust for success” (Record Mirror) to “a god among so many mere mortals” (Tears For Fears’ Roland Orzabal). Elbow’s Guy Garvey described this transformation as being “as impressive as the moon landings”. It’s My Life wasn’t exactly a giant leap for mankind, but it was one small step in that journey towards post-rock visionaries.

After all, in reality, It’s My Life is not so far removed from The Party’s Over. With slick, precise and muscular production, it feels rigidly programmed, even when it isn’t. It’s easy to judge their early output against what they would become – a pitfall even Friese-Greene has succumbed to. Speaking of the single he co-wrote, he said to Jim Irvin in 2006: “I don’t think It’s My Life is a crap song, but you certainly couldn’t say it’s one of the best… it’s nothing to get excited about”. Faux modesty, perhaps. Total nonsense, certainly. It’s as fine a single as anyone could ever hope to write. And that’s nothing to be embarrassed about.

To avoid throwing the baby out with the bath water, It’s My Life (the album) deserves to be assessed on its own merits. For those of us who don’t think pop is a dirty word, does it stand up as a record? Absolutely. It’s not perfect, but it’s a compelling statement that offers up moments of greatness. It’s My Life doesn’t need apologising for and is an impressive record from an ambitious young group brimming with potential, yet still finding the language to fully unlock it.

The Songs

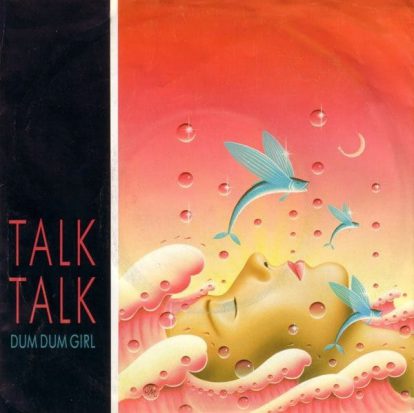

Dum Dum Girl

The album opens on an acoustic piano riff, complete with fluttery flute sounds and percussion instruments, laying a foundation of interesting textures, before segueing into the more standard instrumentation. From here, it’s back to business as usual, with synths set to a driving 4/4 beat and Webb’s bass upfront in the mix. Until, that is, they adopt a subversive trick, so favoured by the Pixies, going full throttle in the pre-chorus bridge before dropping it down to an almost ‘anti-chorus’, stripping it right back once more for the main “Dum Dum Girl” refrain. Here, the vocal delivery resembles a revolving monastic chant at odds with the lyrical imagery. The title is a sly nod to Iggy Pop’s Dum Dum Boys (which incidentally also inspired the similarly named, band Dum Dum Girls). This would be the third (and least successful) single from the LP.

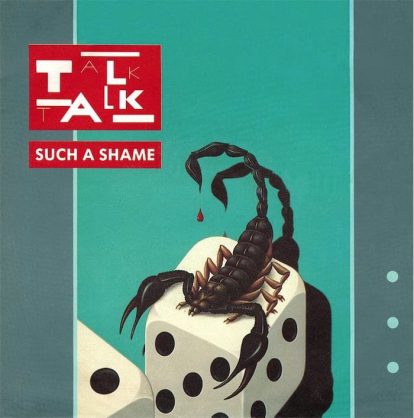

Such A Shame

Lyrically, this early highlight takes its premise from Hollis’ favourite book, The Dice Man by Luke Rhinehart (a dark cult classic in the vein of A Clockwork Orange or Crash). The book presents the account of a psychiatrist who makes life decisions based purely on the roll of a dice, with often extremely disturbing consequences. Echoing Brian Eno’s fabled ‘Oblique Strategies’ cards, Hollis apparently deployed the dice technique himself in writing the lyrics, picking phrases from pieces of paper based on the number he rolled. Hollis’ love of jazz is subtly infused into the rock template, via some particularly muddy piano stabs in the verses.

The album’s second single, it didn’t land in the UK, stalling at No.49. Conversely, it was a huge hit across Europe, helping to cement Talk Talk’s career on the continent, going to No.1 in Switzerland, while just missing out on the top spot in West Germany. It had an extra boost following Hollis’ death, reaching the Top 5 digital sales chart in France. Testament to its ongoing popularity in Europe, it was later covered by German pop artist, Sandra, in 2002, and Belgian star, An Pierlé, in 2013.

Renée

The opening rhythm, though played acoustically on world percussion, assumes the character of an industrial electro drum loop à la Depeche Mode, before chiming arpeggiated chords come in alongside Webb’s rubbery fretless bass. It’s one of the more tender moments on the record, Hollis’ pleading vocal laced with something that resembles longing or regret. It’s also the longest track on the album, stretching well over six minutes. The muted trumpet in the breakdown adds a vaguely jazzy undertone, before bringing it back up a notch for the final chorus, then gently fading out into nothingness.

It’s My Life

For many casual observer, this is the obvious entry point into Talk Talk’s canon; an accessible gateway into a varied landscape. From the opening notes onwards, it’s life-affirmingly wonderful; propelled along by Webb’s throbbing bassline, weaving in and out over washing synths, while Hollis croons sweetly over the top. But its apparent simplicity belies a modulating chord progression that’s more complex than it first appears, demonstrating Hollis’ evolution as a songwriter. While today, it’s an instantly recognisable staple of British classic radio, it didn’t land the first, or even second, time round. Only third time lucky, when it was re-released in 1990 to promote a greatest hits compilation, did it chart at a respectable No.13 (amazingly their highest UK single position).

It had a new lease of life in 2003, when No Doubt covered it for their own Greatest Hits (reaching No.1 in the Czech Republic and Poland, with plenty of Top 10 showings elsewhere), helping them to reach a whole new generation and inviting reappraisal on home turf.

Tomorrow Started

Opening with a repeated drum pattern and acoustic guitar chords, a simple descending synth lead line comes in. Like Renée it’s another slow, melancholic track with a hypnotic and unsettling post-apocalyptic feel, and lots of space in the arrangement for Hollis’ croon. His long, drawn-out notes over washy synths are punctuated by syncopated stabs, once more, highlighting some exquisite fretless bass work from Paul Webb. The track is elevated from potential drudgery by the atonal free-jazz trumpet solo in the final third, a sonic bolt from the blue that hints at what’s to come. It’s one of the tracks that most resembles Depeche Mode in the vocal refrain and the cold, sparse production. Talk Talk at their most understatedly beautiful.

The Last Time

Opening with a bouncy beat and a wonderful nagging synth riff, The Last Time carries all the hallmarks of a potential hit single. But then it never really delivers the soaring chorus it seems to be building up to. That’s not a problem because the smooth, understated refrain is equally effective, albeit in a more reserved fashion – like the audio equivalent of basking in the evening sun in the last days of teenage summer. It’s a subtle and touching moment, that leaves a lingering sense of warmth, long after the gradual fade-out.

Call In The Night Boy

One of the earlier compositions here, Call In The Night Boy was originally developed as a stripped-back piano arrangement, between Hollis and Phil Ramocon. It was one of the first examples of Hollis’ modulating keys, and Ramocon’s playing on the demo brings a jazzy feel, showing a clear taste of the future. If only the powers that be had the guts to put this version out. Alas, clearly it was too much, and it languished as a B-side, only to resurface on 1998’s Asides Besides several years later. The ‘definitive’ version included here is a different thing entirely – an upbeat, amped-up rocker, complete with classic 80s drivetime guitar (or fuzzed-up synth?). Nonetheless, it retains some lovely, avant-garde piano and strange atonal tuned percussion parts that show flirtations with the jazz leanings that Hollis would rate so much.

Does Caroline Know?

Although a foray into world music, opening with bongos then a plinky plonky electric keyboard sound, on first listen Does Caroline Know? comes off unmistakably like elevator muzak. Surrounded by melancholy on all sides, this particular track has such an uncharacteristically upbeat bouncy jauntiness, that it’s hard to tell whether or not it’s an in-joke. On initial impression, it’s the flimsiest track on the record, like a curio B-side. But then every album needs one of these, and its lightness of touch provides a necessary departure from the heavier tone elsewhere.

The wobbly, otherworldly space-age synths sound like Bernie Worrell’s contribution’s to Talking Heads’ recent album, Speaking In Tongues. The track makes more sense in a live environment, with organic textures given space to breathe. Many fans regard the live recordings to be the superior iterations of this track (check out the September 1984 version from Rotterdam available online). The epic ‘guitar’ solo is actually performed by Ian Curnow on synthesizer, while Ramocon provides wonderful off-the-wall piano. One has to wonder whether the title is a cheeky response to Brian Wilson’s Caroline, No from Pet Sounds (which in turn was originally titled Carol I Know).

It’s You

For the album’s closing song, it’s back to business with a driving 4/4 beat, sharing accents in a similar vein to It’s My Life, but set against a jauntier backing track. Some interesting synth flourishes and drum accents combine to push the track forward, but really, this feels like Talk Talk on autopilot. While there’s nothing particular to fault, nor is there anything of particular merit that hasn’t been achieved better elsewhere on the record. It’s not bad, but it’s a little generic and the hook is neither sharp nor strong enough to latch on.

Listen to Talk Talk here

Enjoy this article? Check out our Classic Album feature on Talk Talk’s Spirit Of Eden

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.