When Classic Pop met for its Human League interview in autumn 2024, Philip Oakey, Joanne Catherall and Susan Sulley offered a remarkably candid insight into their usually private world…

It’s 1.59pm on 28 August. Classic Pop is due to meet The Human League at the bar of the Mercure Hotel in Sheffield, chosen because of renovation work on the group’s studio 10 minutes away in the city centre. None of the group are here yet. Their publicist gets up to have a quick look outside for any impending arrivals. As he does so, at 2pm exactly, Philip Oakey, Joanne Catherall and Susan Sulley stride through reception together. It’s the single most impressive way to enter an interview that Classic Pop has ever seen.

“We come as a team,” smiles Joanne, aware The Human League’s arrival is every bit as choreographed as walking onstage: they’re dressed as chicly as if playing a festival, too, rather than for an upscale chain hotel bar.

We gather on two sofas, your reporter and Philip opposite Susan and Joanne, who almost immediately crack up at a guest walking through the otherwise empty bar in his dressing gown. “I know he’s here for the sauna,” says Susan, recovering her composure. “But that looked mad. And the sauna here is shit.” It sets the tone for the next 90 minutes: The Human League might want to treat a rare interview as a performance, but they’re far too unguarded and willing to let people into their world to maintain any real distance.

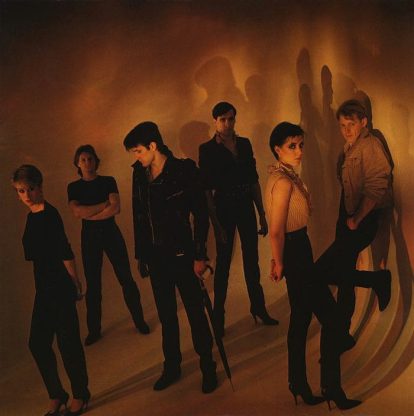

Stage-Ready Team

That the trio look stage-ready doesn’t mean they’re in any kind of uniform. Joanne’s long dark hair is swept back over a black-and-white patterned blouse. Susan – long nails to die for – is in plain black. Then there’s Philip: small neat black beard, shaved head, purple shirt and immaculate black leather jacket. After a summer of festivals, they all appear match-fit. In short, they look exactly how you’d want The Human League to look.

“We’re not the sort of group who lets somebody come in and say: ‘You’re all going to look like this.’ That’s not us,” says Joanne of The Human League’s appearance. “We’re a group of individuals who are collectively The Human League. We look how we want to look. People have tried to style us, but they didn’t get on at all. We are what we are. We always have been.”

Philip believes the group were fortunate they were signed to Virgin: “They weren’t dictatorial, and that was part of their image, when a lot of record companies thought it their right to tell people what to do and how to dress.”

It meant that, once Joanne and Susan joined for Dare, they could present themselves how they wanted. “Part of it was money,” emphasises Catherall. “We didn’t have much money, so we just wore what we wore.” Sulley nods in agreement, adding: “How we looked on Dare, that was literally all the clothes we had. The dresses in the Open Your Heart video were just ones that we’d bought separately from Wallis.”

That ethos has remained in the subsequent 43 years, though Susan clarifies: “We discuss colours. It might be: ‘How about red for this tour?’ or one of us will see something and say: ‘How about this for that part of the show?’ But stylists? No.”

Imposter Syndrome

It’s not quite true that The Human League are what they’ve always been. Oakey – imperious demeanour with vocals to match, absolute bundle of self-doubt underneath – has finally begun to accept what all right-thinking music fans have known since Reproduction: The Human League are as good as it gets.

“I’ve always had this vision that we’d fail,” he frets. “I’ve only got over that in the last 10 years, since the touring side has built up nicer than we ever expected. I always thought I’d end up in Sheffield, walking around with my possessions in a carrier bag, having made a fool of myself. I expected people to laugh at me and say: ‘There’s the fool who thought he was a big popstar.’ I’m only very recently done thinking that.”

Joanne throws a cautionary look: “When Philip says he thought he’d be walking the streets with a carrier bag, that’s a little far-fetched,” but Philip responds: “It really isn’t.” He mentions a disgraced local Sheffield celebrity who “ended up walking around Broomhill, possessions in a bag,” insisting: “I thought that would be me one day.”

Sulley and Catherall are equally uncertain about their status, the latter admitting: “I still have awful dreams about when we’ll be found out, thinking: ‘When is this going to end?’” Susan agrees: “That worry will never leave me. I worry this is all going to stop, and reality is going to hit me straight in the face.”

None of this is delivered as a big confessional. The Human League don’t want you to feel sorry for them. Their attitude is more that none of this should be taken remotely seriously. They’re tremendously entertaining company… The Human League are not, God forbid, earnest rock musicians.

Music For The Masses

Discussing their forthcoming arena tour, Oakey says of planning their setlist: “We’ve got hits we have to do, because we’re not trying to alienate people: we’re not Tin Machine. We want to please the people who’ve been our supporters for decades.”

Joanne continues: “We’re not going to radically alter a song so that people go: ‘But that’s not what I’ve come to hear.’ We’ve all been to shows like that.” Philip laughs: “We’ve toured with people like that. But they’re musicians. They want to prove they’ve ‘advanced.’ No thanks. None of us are musicians.”

Philip Oakey pronounces “musicians” the same way anyone else would pronounce “bin juice”. Later, when Susan discusses the less glamorous side of the music industry, she stumbles over her words when saying: “I know it’s meant to be all rock’n’roll, but, well, ok, not ‘rock’n’roll,’” as Oakey immediately shoots Classic Pop his one frankly terrifying look of ‘I’m Philip Fucking Oakey, mate. I made Dare, remember?’ Every word is very sternly delivered as he thus announces: “Don’t. Ever. Call. Us. Rock. And. Roll.” Consider it noted. As Joanne says: “All three of us have always liked pop music. We want to make pop music. Pop music is a certain mood, and that is not: ‘Let’s put some drum and bass into it to make it sound modern.’”

Tour De Force

That the live side of The Human League has become so important still feels slightly mysterious to a group who didn’t start playing shows properly until Octopus in 1995. All three are still mortified as they recall their first tour together for Dare. Joanne recalls: “We did one tour and Virgin went: ‘Guys, don’t do that again.’ It was: ‘That was really bad. People don’t want to see that.’ We toured again for Crash, but that was just as bad.”

Still the trio’s manager 30 years on, Simon Watson, urged the League to work out how they’d feel comfortable onstage once Octopus returned them to the charts. “We’d been quite punk about not playing live,” remembers Philip. “Being told: ‘You’ve got to learn how to do this,’ it petrified us. But it changed everyone’s viewpoint. We worked our way up, playing four down the bill in the States to dance acts.” Susan: “We needed to work our way up, because we were terrible at first.”

Sulley explains: “This coincided with a time when we were supremely unfashionable. We’d be in the Midwest of America, thinking: ‘What are we doing here?’” While The Human League rightly headline arenas and festivals back home, Oakey believes parts of the States are still reticent to the group’s charms. “I’m trying to think of where we fit in America,” he considers. “Glam was never a thing there, as it was treated more like metal. Marc Bolan only had one American hit, and it can feel like that for us, too. Places like New York and Los Angeles get us, but sometimes people aren’t ready for it. And if you’re not ready for us, people just look at you and wonder why we’re doing what we do: ‘Why are they changing costumes? What is this?’”

Dare To Be Different

Nearly 30 years on, touring is mostly a blast. “It’s not a bad job,” laughs Susan. “I get to go away with my mates for a few weeks, and then I get to play onstage in front of all these people.”

Playing live has even made Philip appreciate Dare. Yes, reader, you are probably well aware that Dare is up there with the Pyramids and the moon landings. Mention Dare to Oakey, however? “I’ve always thought it’s a bit bleak.” WHAT? “When we last played Dare on tour, I began to see your view a little more.” Phew.

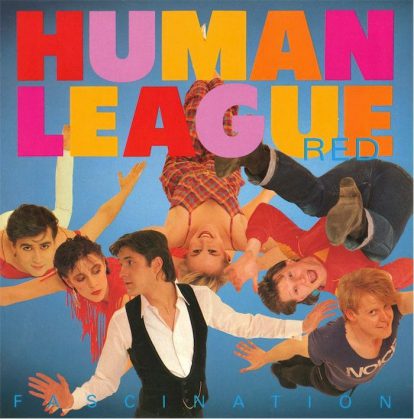

Catherall says: “It’s weird to hear Dare in full. Obviously, you’ll hear Love Action and Don’t You Want Me on the radio. But Radcliffe and Maconie played Sound Of The Crowd all the time, and it sounded really weird. It made me think: ‘How did we get away with that?’” Philip smiles: “I agree. Sound Of The Crowd is one of the weirdest singles to have ever done well. It’s not O Superman. But it is weird.”

Top Of The Pops

Where even The Human League agree that The Human League were geniuses in the lead-up to Dare was in bringing Joanne and Susan into the group. (Never “band” – The Human League call themselves a group.) After Martyn Ware and Ian Craig Marsh scarpered to become British Electric Foundation, it was inspired of Oakey to ask two young students spotted on the dancefloor at Crazy Daisy’s in Sheffield to become co-conspirators in storming Top Of The Pops.

The big question is: how did Philip know that The Human League needed two total newcomers in order to make a masterpiece? “I did it precisely because it was a leap,” he explains. “I wanted an innovation and thought we should get someone new, and I wanted to get a singer instead of a guitar. We hadn’t bargained on getting two people instead of one, but here we are.” Referring to cult author China Miéville’s alternate viewpoint novel The City & The City, Philip goes on: “Once you start thinking of having two people, you’re in China Miéville territory. Or a Twix. If I ever write another song, it’s going to be about China Miéville’s favourite chocolate bar.”

Together Forever

That the trio are still together, and still clearly proper mates, is something that couldn’t have been predicted in 1981. “I thought this would only last two years, maybe three if I was lucky,” insists Sulley. “Becoming long-term was never the plan.”

For all their self-deprecation, the trio are proud they’ve lasted, as Joanne reasons: “There are steps along the way that can look like mistakes. In the end, all those steps are probably the right ones. I haven’t got a limousine waiting outside this hotel, and my car hasn’t passed its MOT. But you can sell your soul to the devil and give up your integrity. We have kept our integrity.”

Staying in Sheffield has been key to that integrity. Pleasingly, Philip and Martyn Ware are on good terms these days. They had lunch together shortly before lockdown, as Oakey reveals: “I thought lunch would become a regular thing. It didn’t quite, but Martyn doesn’t live in Sheffield, so it’s hard to find time.”

At their height, The Human League were advised to leave Sheffield to become tax exiles in Jersey. “I had crying sleepless nights about the prospect,” Joanne remembers. “We all thought: ‘Why would I want to live in Jersey?’ We didn’t even have any money – management insisted that we would if we went there.

“We’ve never tried to do a tax dodge. I look at people who get caught out and I just think: ‘Why?’ We’re all very straightforward, working-class people who want to support other working-class people by paying our taxes.”

Rise Of The Machines

In the early days after Susan and Joanne joined, they had a manifesto pinned to their studio. Philip can’t remember what it stated, claiming: “It was probably: equality, fraternity and analogue synthesizers.” He’s joking, yet the fraternity has stayed in the group. So have the analogue synths.

Oakey has lived in the same house in Sheffield all his adult life: you can see it on the inner sleeve of Hysteria. The 1986 documentary Private Eyes shows the group at Philip’s home, when he and Catherall were a couple. There’s even a Sinclair C5 in the garage: “That went at the same time as my last motorbike,” he reveals. “I didn’t get to drive it much. I drove it into the garage door and it stopped working.” Now, he describes his home as “a Steptoe’s yard of modular synthesizers – I only drive a Skoda, but I’ve got a collection of really nice synthesizers.”

Asked if there’s a dream synth he doesn’t yet own, Oakey immediately replies: “A Roland System 700,” as Joanne tuts: “Oh good lord… Every single day on tour, there’s a point where Philip, Dave our studio manager, and Graham in our crew will sit there on their phones, going: ‘Have you seen this? Someone is selling an SP404!’ Me and Susan will look at each other, because it’s the same every single time.”

The fact Philip owns so many synths leads to an obvious question: is he using them to write new music? It’s been 13 years since The Human League’s previous album, Credo, of which Oakey considers: “We should have made it a little happier and poppier. That is entirely my fault, as my aim was to do a synth album that sounded like synths.”

Moving Forward

On the prospect of future music, Philip explains: “I write lyrics down every couple of days. I’ve got a little arpeggio going on a synth I’ve had for about three months that I’ve not recorded yet. Finishing a song? Things get in the way a lot now.”

Philip is honest that there isn’t the motivation to get an album made anytime soon, saying: “There isn’t the drive to do it when you know it isn’t going to make you any money. When we’d record an album for 18 months or four years, it was seductive to know that, at the end of it all, 100,000 of them would be made and put in HMV. This thing would be available and you’d know how many of had been bought. “We’re supposed to do that in all sorts of other ways now, and I still don’t quite understand how digital music exists in the air. So it’s quite hard to want to do it, to make an album.”

Philip is similarly unsure of the motivation to collaborate with other vocalists, despite making great duets with The All Seeing I, Kings Have Long Arms and Pet Shop Boys, of whom he says: “I think we inspired them to do one-word album titles. They’ve had some better words than our titles, and they’ve had more albums than us. I love Pet Shop Boys.”

His general view on collaborations is: “I don’t know that it’s really my thing. It starts out with someone saying: ‘We think you’re a great singer,’ but it ends up with: ‘Can you do an interview with us in The Sunday Times so we can get some notice?’ I do it, then no-one buys the song anyway.”

Dream Job

Of course, Oakey featured on one of the best collaborations of the 80s, when he sang Together In Electric Dreams for Giorgio Moroder.

As deadpan as his words can look in print, the look of unabashed joy on Philip’s face when talking about Giorgio is beautiful. “Giorgio was very efficient,” he beams. “Electric Dreams was done in four days, when Giorgio didn’t like to work before 11am, nor after 4pm. He hates overdoing things.

“I sang Electric Dreams twice. After the first one, Giorgio said: ‘Great, we’re finished.’ I said: ‘Hold on, what if anything went wrong? I should do another one for safety.’ ‘Well, OK then.’ And that was it.

“Giorgio’s theory is that, if you have to do a song over and over again, then ‘This song is not for you.’ I was supposed to sing The Never Ending Story, too. I sang it a couple of times, but Giorgio said: ‘This song is not for you.’ It’ll come out at some point – and then you’ll hear that song: it wasn’t for me. I like the Limahl record. The Never Ending Story, it was for him.

“I’m just happy I’ve worked with Giorgio, as he was our absolute hero when The Human League started. More than anyone else, he had the path for The Human League to follow. We just tried to make music that was as good as Giorgio Moroder.”

Jam & Lewis

The revelation that there’s a demo somewhere of a second film theme with Moroder is topped by another what-if: Crash was nearly produced by Stock Aitken Waterman. While waiting to hear if Jam & Lewis would work with them, the group met Pete Waterman.

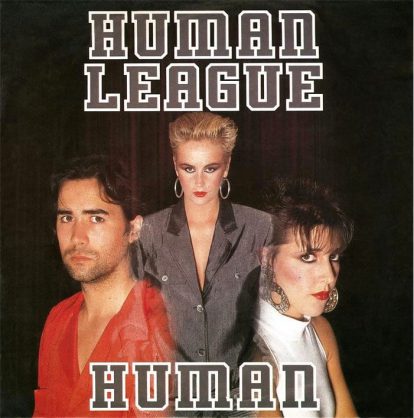

Oakey says: “At that time, Stock, Aitken Waterman had only done Princess’ record, Say I’m Your No.1. Then Jimmy and Terry said yes, and Pete Waterman told us: ‘You should go for the real thing.’ He was right, in that Crash is a very Jimmy and Terry record.”

The general view of Crash is that The Human League felt dominated by their producers, who wanted to sideline the group in favour of session musicians and their own singers. That is not the view of the trio now, though Philip says of their former collaborators: “Jimmy and Terry were brilliant with the singers, but ruthless with the musicians.”

Catherall enthuses over the experience: “They taught us how a studio works. Their studio wasn’t somewhere fancy like Air or Abbey Road, it was just a building in Minneapolis. We came back from Crash with a real vigour to build our own studio, so we did.”

Crash Landing

The actual recording was more fraught, however, as Joanne says: “It was scary. Standing in the vocal booth, I’d think: ‘Look at who these two have worked with. I’ve got to compete with them?’ But they were incredibly lovely about my singing. If they’d been Giorgio Moroder, they might have said: ‘This song is not for you’ about every single song.”

Sulley agrees: “They spent so much time with the three of us. If you weren’t getting a song, it was just: ‘Let’s just stop and have some food.’”

It’s only in hindsight that Philip appreciates how vital Jam & Lewis were: “They’re the only producers we worked with who also wrote songs. Them writing songs, it gives Crash a different dynamic. We didn’t properly understand that at the time, and we never said thanks. Joanne is right, their studio was just an old photographic studio. But it helped that they were natural geniuses with sound. If you’d put a boombox in front of the two of them, they would have created something that sounded incredible.”

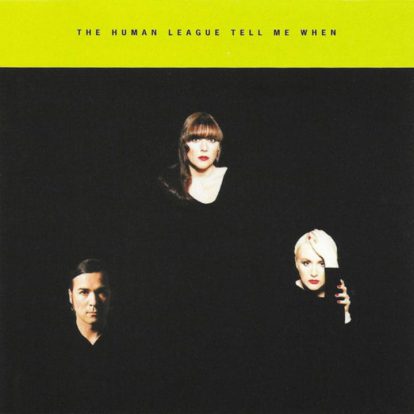

While Crash spawned their second US No.1 in Human, Philip names Octopus as his favourite overlooked Human League album – “I love its sound” – while Catherall picks Secrets: “Amazing reviews across the board, a brilliant piece of luck to work with Toy as producers, a great record company in Papillon. It felt like the perfect mix. Then the Papillon guys got ousted and the actual release was a damp squib. That’s a fantastic record, though.”

Anymore Secrets

Fans waiting for boxset editions of any of the Human League albums shouldn’t get their hopes up. “I think we’ve mainly released the songs that are in the vaults,” considers Oakey. “We aren’t like Prince.”

Catherall explains: “We didn’t have that much music when we went into any of the albums, so there’s not a lot of music going spare.” “There was always just enough by the end,” adds Sulley.

Mention that Credo now fetches £300 on vinyl and Susan exclaims: “I’ve got some spare copies in my house!” Philip recalls: “That’s the album where the warehouse closed down immediately it came out, isn’t it? Our manager will have Credo planned to come out as a vinyl edition at some point.”

One special edition the band are planning is a version of Dare in Atmos. The trio have been down to Abbey Road to hear it, and Philip explains: “I think that’s coming out soon. Atmos is very specialist. I’m not super on it when it comes to 3D sound, but if people want to hear Dare in 3D on their headphones, that’s okay.”

There isn’t any chance of an appearance of Romantic? produced by William Orbit, before future Moloko mainstay Mark Brydon took over. “William locked us out of the studio,” claims Joanne. “We were banging on the door, but he was: ‘You can’t come in!’ I think he kept all the mixes and I can’t imagine he’ll let us have them.”

It’s time to let The Human League leave, striding out together as impressively as they entered. As Joanne concludes: “As soon as the festivals are over, we say to each other: ‘What happens if nobody wants us next year?’ We’ve already got some booked in for 2025. That’s such a relief.”

They shouldn’t worry, of course: those big concerts – they are for you.

For more click here

Read More: The Lowdown – The Human League

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.